Photo: Per_4708-m

The Back Story: The importance of connecting a city vision to the physical

25 January 2021

In this series, Per Grankvist, Chief Storyteller for Viable Cities, explores how cities can use the art of storytelling to engage citizens in climate action.

In a fairy tale, everything happens once upon a time and takes place somewhere carefully stated, but carelessly described.

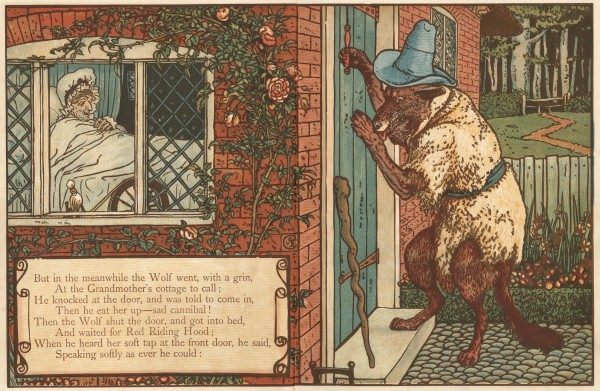

In Little Red Riding Hood, she meets the wolf in the woods, on her way to see Grandma, whose house stands under three large oak trees. The Brothers Grimm have not included any further details about the house, nor will we ever know what the forest is called.

It is a clever narrative approach: when descriptions are general, we make our own image of these places based on our experiences. Everyone has a picture of a forest, a house in a forest and a grandmother in memory, and the brain uses these pictures to make the story of Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf real.

Polar bears on melting ice floes is admittedly a very arresting image (and often chosen for this reason), but since so few of us have experienced that situation, it is difficult to relate to it and the image remains just that – an image.

Another way is to use graphs which show sharp upward ticks or alarmingly steep falls. Alternatively, just facts can be presented: sea levels could rise by between one or two metres by the year 2100 if the world’s biggest ice sheets melt. This is also difficult to understand.

But if I ask you to remember a jetty in a port that either means a lot to you, or that you visit often, and then ask you to think about what that place would look like if the water there increased by one or two metres, then something happens. Climate change is becoming more real because you have anchored it to a place you know well.

It’s not that weird. We are shaped as people by the places we grew up and with which we have strong memories. The stories we have heard about how these places shaped those who live there are impressed upon us. We use all this as references to understand ourselves, others and new places we visit.

Last spring, I was asked by the Scottish Government if I, together with a group of international experts, wanted to share views that would contribute to making Scotland’s way of talking about climate change more effective. Since the country’s climate goals are among the most aggressive in the world, it is understood that society as a whole will need to embrace the great changes that are needed.

In the draft strategy I was asked to provide input on, I was impressed by the ambition, but objected that it was too general. If you want to make the population understand that climate change is important, you should not say that it has positive effects for humanity, but point out how it benefits the Scots. The arguments may be the same, but in the latter case it will be perceived as both more concrete and more relevant.

In the same way, it will be perceived differently if the country’s green transition creates “46,000 jobs” than if it creates “46,000 Scottish jobs”. The difference? A connection to a physical place.

In Umeå, the river and the forest are recurring elements in stories about the countryside and the city’s development. If you want to get people to switch to renewable electricity, it can thus be more efficient to say that the energy comes from the river, than that it is green. A place always trumps a concept, which is probably the reason why fairy tales so rarely use concepts.

By linking the desired change to the place, to the shared experiences that are there and to the residents’ perception of themselves, the message is perceived as more concrete, relevant and important.

Gothenburg has time and time again been a pioneer in adjusting its industry to new conditions.

In the design of the city’s climate contract, project manager Carl Mossfeldt told me that he took into account the pride that exists in this adaptability. The city therefore talks about “a green industrial transformation” in Gothenburg in particular, rather than the importance of climate change in general. This strong narrative has ensured that the issue will be considered relevant to discuss in political circles because it relates to history, but also to the future and survival. It also means that the parties that do not usually talk about the climate issue can discuss it without it being politicised.

In a pilot project in Malmö, I am testing a new methodology for engaging citizens in climate change through relevant stories. The goal is to show us that it is possible to live tomorrow’s good life within planetary boundaries, already today. In the script, there are events which have the express purpose of anchoring the story in common local references. Most Malmö residents can relate to a bicycle being stolen, and therefore it is also included in one of our stories.

This helps the story of tomorrow’s behaviour not to feel like a fantasy, but like a fairy tale that becomes real, because we can relate to it. If we want to place the fairy tale about Little Red Riding Hood in Malmö, the scene where she meets the wolf has to be set somewhere other than in a wood, because there aren’t many woods around. And Granny’s house would have to be set under three beeches rather than oaks. Even fairy tales have to include references one can relate to locally in order to be believable.

Other stories worth mentioning

- The story of Little Red Riding Hood comes in a large number of varieties. Smithsonian have identified 58 versions, many of them thousands of years older than the version by the Brothers Grimm. Scientists at the Radboud-university claim to have found more than 400 versions.

- The city library of Toronto has many versions of the saga in its collections. Here’s a fun rundown and comparison.

- How various artists have portrayed Little Red Riding Hood over the past centuries says more about them, their ideals and the time they lived in than about the saga itself. Likely, a similar comparison could be made on how “the city of the future” has been depicted at various points in time.