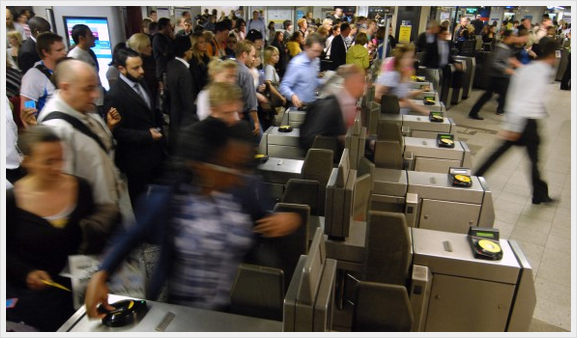

Photo: Transport-for-Londona

Why travel cards are smart business for cities

25 September 2013

by Richard Forster

As public transport ridership increases due to the growth of urban populations, cities are looking at more efficient ways of coping with demand. Jonathan Andrews explores the development of smart card technology and the rising business case for cities to use them

In June, London celebrated the tenth anniversary of its smart travel card. While it might have taken time to get used to the name–Oyster card–busy Londoners warmed to its ease of use and time-saving convenience.

With some of the infrastructure on London’s metro, or tube, dating back to the 1850s, Transport for London (TfL) had to look for ways of increasing efficiency at the gateline without widening station entrances and the number of gates–thereby avoiding the need to purchase more expensive central London real estate.

“The business case was quite clear for us,” recalls Matthew Hudson, Head of Business Development, Customer Experience at Transport for London. “The 1990s saw such an increase in ridership on the London Underground network that our customers were facing delays due to congestion at the gateline. In order to increase throughput at the gateline we had two choices: to extend the gateline or to invest in new technology to speed the process up.”

The technology argument won, albeit with some considerable risk. Smart card technology was still relatively new at that time, with Hong Kong being the only other large city to have rolled out a similar system.

Ten years later the investment seems to have paid off. Eighty-five percent of all rail and bus travel in London is now paid for using an Oyster card, with seamless travel permitted between all forms of transport on the one card. This has eliminated the need to queue for purchasing tickets at stations or from bus drivers and conductors, ensuring faster boarding times and a speedier service.

“Our busiest station, Liverpool Street, handles more than 25 customers per gate, per minute, in the morning peak, and there are a further 20 stations that exceed 20 customers per minute,” says Hudson. “Under the old ticketing technology [paper tickets], 15 customers per minute was the maximum.”

Further benefits include a reduction in fraud, with revenue lost due to non-paying customers, or ‘irregular ticket usage’, falling 2.5 percent, making a £40 million saving per year since its introduction.

Overtime, Oyster card evolved to passengers’ needs and offered in 2005 daily price capping, automatically calculating and providing customers with the cheapest fare. In 2012, Oyster Online Accounts was launched to allow customers to be able to easily manage their accounts online.

Yet, such an expansive and overarching system is not without fault. The huge infrastructure costs of implementation and the complicated ticketing systems, between different and competing operators, did extend the rollout time.

It wasn’t until 2010 that Oyster cards were accepted on all commuter rail services within Greater London, with Thames river services only accepting Oyster cards from March this year.

“While not buying a ticket in advance is a great benefit to customers, this adds cost and risk to operators, particularly when there is more than one operator,” adds Hudson. “Often it is the commercial agreements between parties that inhibit the delivery of smart card schemes.”

The need for commercial cooperation

In 1994, Hong Kong tackled the need for such agreements by establishing a joint venture between the five major public transport operators, later to be named Octopus Cards Limited. Dubbed ‘co-operation within competition’ the agreement allowed the technology to be tested for three years across the operators before a complete launch in 1997. The Octopus Card enabled commuters to travel across multiple public transport modes using one single card, eliminating the hassle of paying for each individual journey.

“The system was developed, managed and owned by five transport operators which, despite competing for passengers, have all worked together in the interests of the public to ensure a seamless payment system,” says a spokesperson from Octopus Cards.

In Sydney’s case the lack of cooperation combined with a failure to simplify tickets and fare structures caused extensive delays in the rollout of its smart travel card. Originally intended to be implemented before the 2000 Sydney Olympics, it was only in August this year that the first steps of the rollout began.

A crucial component of the failure was Sydney’s unsuccessful attempts to overhaul its complex and out-dated ticketing system. Fifteen years of delays and legal action between the New South Wales State Government, that oversees Sydney’s transport, and the contractor, then known as ERG, was only resolved last year in an out of court settlement, sparing the city a “potential loss of around AU$200 million [US$179 million]”, said Gladys Berejiklian, the new Transport Minister.

With a new partner in Cubic Transportation Systems, Sydney, in August, began the rollout of the Opal smart travel card on its ferry network. A progressive rollout on train and bus services is due to begin by the end of this year.

“Come 2015, 40 ferry wharves, more than 300 train stations and more than 5,000 buses and light rail will have Opal equipment operating in Sydney and regions,” says a spokesperson for Transport for New South Wales.

A full smart card for citizens

While Hong Kong’s Octopus consortium led the way for smart travel cards, it also soon realised the card’s vast commercial potential. In 1999, the company offered reloading services in retail shops and automatic top-up by linking bank accounts to the card. And in 2000 it began accepting non-transport business.

“Octopus is not just for travel,” explains Amy Benger, human resources project manager for one of the big four accounting firms, Hong Kong resident, and regular Octopus user. “You can use it in merchants as well, supermarkets, 7-Eleven convenience stores, takeaway food stores, and even my local dry cleaner.”

The handover of Hong Kong back to China in 1997 led to a steady rise in visitors from mainland China. Keen to tap into this market, Octopus was gradually extended to cross-border bus travel and by 2006 was accepted in retail shops in Shenzhen and later in other locations in the surrounding Guangdong province.

In London, smart card technology took a different development path. Rather than pushing the Oyster card as a currency in its own right, TfL gradually updated the card reading technology to accept contactless debit and credit card use. Small payments of up to £20 can be made by waving a contactless credit or debit card in front of the Oyster card reader without the need to enter a PIN.

“What we are doing is offering our customers a different and, for some, a more convenient way to pay,” explains TfL’s Hudson. “We have taken advantage of a product that the payment card industry were investing in, Contactless Payment, and are adapting this for our customer’s benefit.”

Launching the first phase in December last year on London’s buses, TfL reports that over 3.5 million transactions have been done. The rest of the transport network, including Underground, Overground rail and the light rail service will see the contactless technology updated into their smart card readers from early next year.

“We will continue to implement the lessons we learned from Oyster and spend time, this year, testing and educating our staff while also raising customer awareness,” adds Hudson.

Customer awareness and trust is one key component on whether a new payment method is deemed successful. Just last month a report by the UK’s independent passenger watchdog, London TravelWatch, commissioned from AECOM, reported that passengers are still wary and unconvinced by the possibilities of contactless and mobile payment technology regarded by them as too recent and not fully tested.

“Our customer research came to a different conclusion in terms of the willingness of customers to use contactless payment cards for travel,” argues TfL’s Hudson. “However, the report is right in highlighting the importance of customer education. This is all about giving our customers choice over how they pay for travel.”

Other concerns have been raised about a move towards a comprehensive system of contactless payment. These include disadvantaging those passengers without a bank account. Hudson is adamant though that the Oyster card would not be made redundant and would still operate alongside other payment methods in the future.

Exploiting the technology

Hong Kong’s Octopus joint venture began exporting its technology and experience as early as 2003 to the Netherlands, and later in 2007 to Dubai. Rotterdam and Amsterdam now offer an e-ticketing system, developed and supported by Octopus, that is now being rolled out across the Netherlands.

“Today we are successfully serving metro, train, bus and long-distance rail transport with more than 12 million cards in the market and over 2 billion transactions per year,” says Gerben Nelemans, Chief Operating Officer, at Trans Link Systems in the Netherlands. “Octopus not only supports the day-to-day operations of our company but is also a solid partner in development projects regarding future enhancements and expansions of the OV-chipkaart [as it’s known in the Netherlands] such as the use outside public transport.”

London too has exported its knowledge. The consortium that now runs London’s Oyster card is behind the implementation of Sydney’s Opal card. Although more coy about naming particular cities, TfL is still keen to share its experiences with other transit authorities.

“What is important for us is to continually look for ways to deliver value for money in our business and commercial exploitation is one of those,” says Hudson. “We are also talking to suppliers of Automatic Fare Collection systems to see if there is commercial opportunity for TfL to commercially exploit some of the intellectual property we have created.”

What comes out from all three cities’ experience is the importance of having a clear business case.

“Decision makers need to be clear about what they are trying to achieve from the introduction of smart cards,” says Hudson. “And transport officials need to be clear what the costs are of achieving those aims.”