Photo: john-towner-unsplash

Why the 15-minute city continues to inspire municipal leaders

22 October 2024

by Christopher Carey

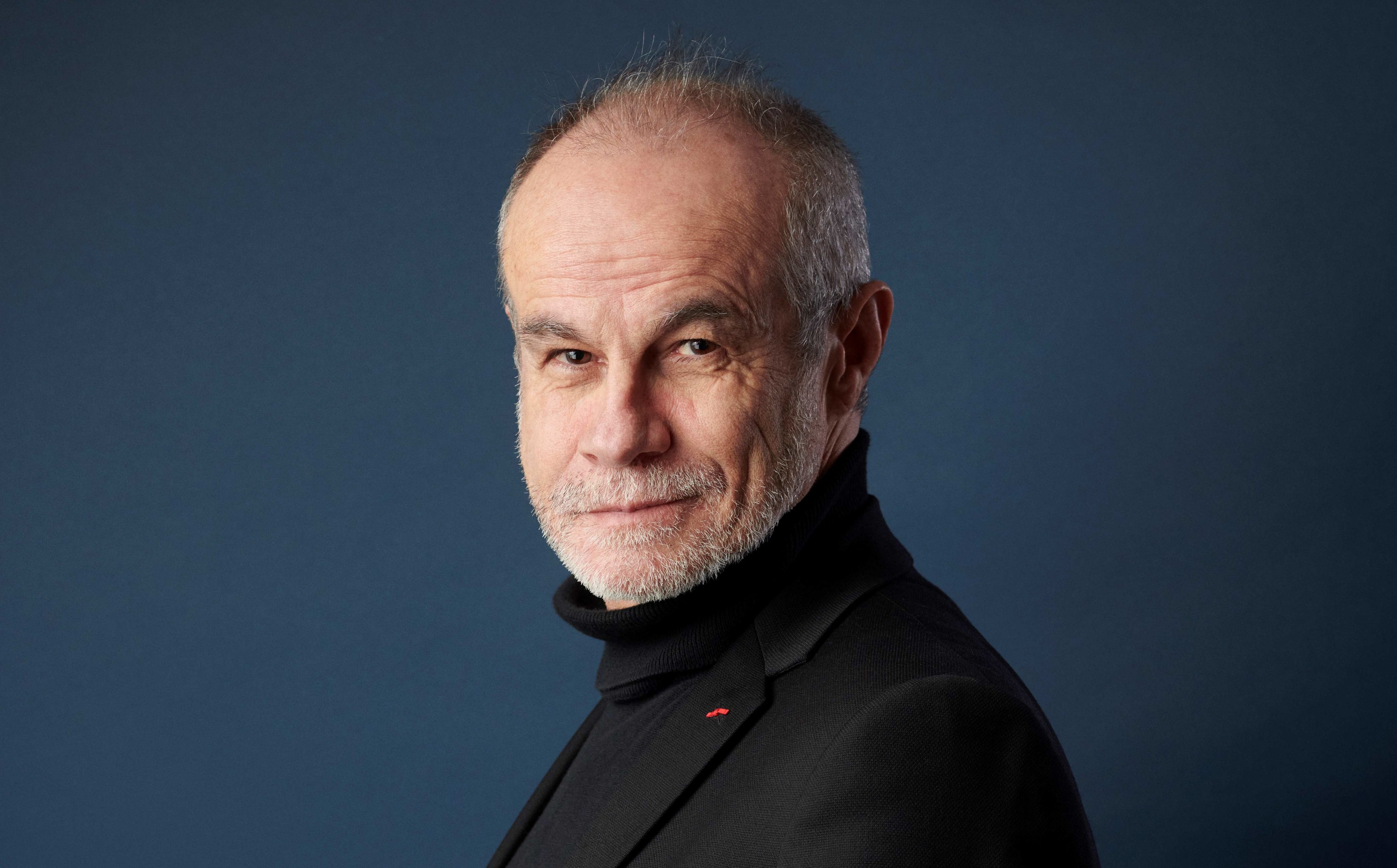

Christopher Carey spoke with Paris’ special envoy for smart cities Carlos Moreno about how his 15-minute city concept has evolved as municipalities continue to adopt his thinking despite a backlash on social media.

After enduring a wave of conspiracy theories during the COVID-19 pandemic, the 15-minute city is proving to be a resilient concept.

Based on the work of Carlos Moreno, a professor at the Sorbonne University in Paris and special envoy for smart cities for the mayor of Paris, the idea has a simple premise – city dwellers should be able to access most of their basic needs within a 15-minute walk or cycle.

The approach aims to reduce dependency on cars, promote healthy and sustainable living and improve the overall quality of life for residents by having necessities including grocery shops, childcare, schools, workplaces and healthcare based within neighbourhoods.

While its origins go as far back as the 1920s, the concept became increasingly popular during the late 2010s and has been implemented in cities globally, including in communities in Barcelona, Paris and Melbourne.

But it was during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many cities seized the opportunity to reorganise their empty streets (and in many cases take space away from cars), the idea took off and, at the same time, became fodder for conspiracy theorists.

Claims that people would be confined to zones were exacerbated in the UK when some cities implemented controversial traffic measures which restricted car use on smaller neighbourhood roads.

The lines between these Low Traffic Neighbourhoods and Moreno’s concept became blurred, leading to a confusing array of online theories – some of which then filtered into mainstream discourse.

Several UK cities have subsequently moved away from the 15-minute city label due to the negative connotations generated online, with Oxford city council (who have largely embraced the concept) removing the phrase from their Local Plan 2040.

For Moreno, who has recieved several death threats and accusations of being part of a WHO-led plot to control how people move within cities, the backlash was “entirely driven by social media” and not reflective of the changes being made on the ground or what has happened since.

“During the last year, we have deployed this [15-minute city] concept in lot of places around the world,” Moreno told Cities Today.

“In the UK, we had the backlash in cities like Oxford for example, but the local elections which followed this were very positive for mayors that have embraced this concept.”

The X-Minute city

Even before Moreno coined the term in 2015, major European cities were already reflecting the ideals of the 15-minute city.

For decades Amsterdam has championed a bike-centric city that is walkable and has good access to public transport.

The same can be said for Stockholm and Copenhagen, with many basic necessities generally found within a 15-minute walk or cycle.

Last month, a report published in Nature Cities analysed over 10,000 global cities using open-source data to assess where each fits within the 15-minute framework – mapping how far residents were from different services, including shops, restaurants, education, exercise and healthcare.

Through an online dashboard, the study showed that European urban centres were far more likely to meet the criteria, with density a key factor.

Researchers noted this could be attributed to the fact that these cities were built centuries ago, long before cars.

Looking at how the concept is applied globally, Moreno says that given each city’s different size, topography and individual characteristics, it may be time to revaluate the emphasis on “15-minutes”.

“The 15-minute city has become the X minute city, because we have a lot of different implementations around the world and each one of these is specific to the local context.

“For example, there’s a wonderful implementation [of the concept] in a small town in Poland with 15,000 inhabitants, but this is so different to Melbourne’s implementation of the 20-minute city.”

When asked who he believed was leading the way in making cities more people-centric Moreno was coy, but said Paris and Milan have made some of the best strides in Europe in recent years.

Looking towards the US, where typically cities are more sprawling because of the car-centric culture, Moreno singled out Cleveland, Ohio.

“This is a city at the core of the country’s automotive industry, but the mayor’s implementation of the concept is just amazing.”

During his first State of the City address in April 2022, the city’s mayor Justin Bibb said he wanted Cleveland to be “the first city in North America to implement a 15-minute city planning framework, where people – not developers – are at the centre of urban revitalisation.”

The city has since embarked on changes to zoning and building codes to encourage dense, walkable, transit-oriented neighbourhoods.

Challenges

For all its promises, the 15/X-minute city has challenges.

The most obvious being how do you fundamentally transform a city that has already been built – particularly those built around the car?

For Moreno, the concept is multifaceted and not just about changing the physical infrastructure, but also changing the way planners think about their city holistically.

“Firstly, we need to break the dependency on the car, and switch from a car city to a human city. This involves embracing active mobility while improving the capability of public transport.

“Today, in the 21st century, the idea that the car is a symbol of freedom and independence is no longer viable.

“The majority of trips made in cars are for short distances, under six kilometres. Of course, the question is not to have a battle against cars, the question is what are the circumstances in which cars are being used?

“Secondly, we need to re-localise jobs and develop local employment. For example, when looking at real estate in cities, we need to switch towards multipurpose buildings.”

While the cost barrier has been cited as an issue by some planners, Moreno says that wider consequences such as climate change and health need to also be considered.

“These implementations are less expensive than the impact of climate change, this is very clear.

“At the same time the implementation of these projects doesn’t have to be expensive – instead of continuing to build on the outskirts [of cities] and build more roads, we can redeploy more funding to create compact, dense cities.

“We also need to ask what are the other costs we’re seeing five years down the road in terms of the impact on health – I think these [interventions] ultimately will cost less in the long term.”

Image: john-towner-unsplash