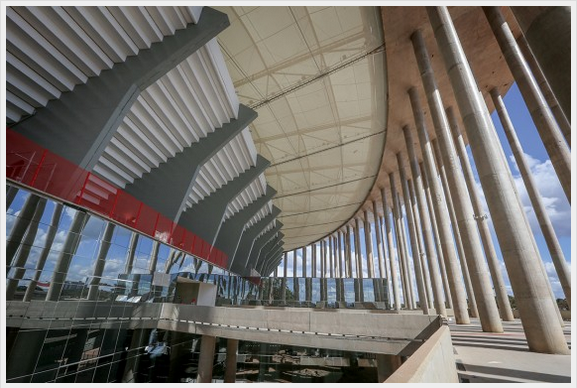

Photo: Lula-Marques

The new cathedrals of football

25 August 2014

by Richard Forster

Richard Forster reports from Brasilia, which following the successful staging of seven World Cup matches, is bidding to have its stadium officially rated the most sustainable in the world

While Brazil may have failed on the football pitch–and the humiliation at the hands of eventual World Cup winners Germany will live long in the country’s memory–its stadiums have shown that when it comes to sustainability, Brazil can match any other country.

Seven of the twelve stadiums built for the World Cup have already achieved LEED certification, something Germany was unable to achieve when it hosted the tournament in 2006.

LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) is a ratings system awarding points to buildings for their sustainability in terms of design, construction and management based

on a system developed by the US Green Building Council. The ratings go from LEED certified (40-49 points) through Silver (50-59 points) and Gold (60-79 points) to Platinum (80 points and above), which is the highest level awarded.

The stadium in Salvador is LEED certified while those of Fortaleza, Recife, Manaus, Porto Alegre and the Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro are all LEED silver rated.

Belo Horizonte announced during the World Cup that its stadium had achieved the holy grail of a LEED Platinum rating, only the second stadium in the world to be awarded that after the Apogee Stadium at the University of Texas in the US.

“This is the first World Cup with stadiums certified with the LEED seal, an outstanding tool to measure sustainable building practices from initial project design through to construction and the start of operations,” says Felipe Faria, Director at the Green Building Council of Brazil.

The national stadium in the capital Brasilia is also seeking Platinum certification led by Ian McKee, who has been on an evangelical mission since Brazil was awarded the World Cup, to get the stadium designers to build with sustainability in mind.

McKee, a former Goldman Sachs banker who was born in Brazil but studied in the US, began his quest to influence the construction of the new stadiums in 2009 when he presented his Copa Verde (Green Cup) plan with architect Vicente de Castro Mello. His aim was to persuade the designers and constructors of the new stadiums to leave a symbolic, sustainable landmark, as part of the transformation of Brazil into a green and efficient economy.

“Noone knew about it or was interested in it or understood it but we told people the stadiums should be certified then the US Green Building Council got involved with the Brazilian Green Building Council,” says McKee, a LEED Accredited Professional. “We gave a pitch to all the designers together then went to the Green Building Council of Brazil and they were already working on the bid for the Olympic Games and they were able to include LEED certification as part of that bid.”

Not content with courting the stadium designers and architects, McKee also lobbied the government to enable the stadium to be able to use net metering whereby a building can generate its own energy and supply that energy to a grid. “In the case of Brasilia, we pursued this with the Ministry of Energy to make sure the legislation for net metering was in place,” says McKee. “It is the first zero net energy stadium in the world which produces more energy [from solar panels] than it consumes.”

One actor he did not lobby was FIFA, which despite FIFA President Sepp Blatter tweeting that Brasilia’s stadium was “a real, tangible, World Cup legacy”, did little according to McKee to support his and the design teams’ vision to make the stadiums sustainable. There were no requirements for Brazil for LEED certification or for green credentials with regard to the development around the World Cup but that will now apply for stadiums built for 2018, with FIFA requiring stadiums to be LEED certified.

“FIFA leant very little or no support. When it come to LEED and sustainability that is something for the next World Cup and FIFA is going to really have to look internally and start to understand what sustainable stadium design is all about,” says McKee.

Future events

While the legacy of the national stadium is clear in terms of sustainability, it is less clear how financially the stadium will work going forward.

The 1.4 billion reais (US$613 million) invested in the national stadium, which is named in honour of the Brazilian football legend Mané Garrincha, means that a professional operator needs to be found which can attract the events to make a credible business of the new stadium. At the moment, the stadium continues to be operated by the local city government.

Nelson Aguiar, International Communications Manager for the Brasilia city government, says Brasilia’s local newspaper Correio Braziliense called the stadium a “golden elephant” in answer to the criticisms, which have been levied against Brazil’s new sporting arenas. According to FIFA, since the stadium was inaugurated in May 2013, it has attracted 1.3 million spectators to 51 events: 37 matches, four concerts and 10 institutional events. This is close to four times more fans than the previous stadium hosted in 36 years. Aguiar says that revenues for the period June 2013-2014 were R$3.2 million (US$1.4 million).

But while soccer may have been a major driver of this, the stadium will have to work hard to maintain this level.

“You really cannot make money just with soccer and that is not just in Brazil,” says McKee. “With the few exceptions of the huge clubs, you need daily events, conferences, a food service plan in place and concerts coming through.”

One of the key issues is Brazil’s ban on the consumption of alcohol at football matches, which was handily suspended for the tournament given US brewing group Budweiser’s hefty sponsorship of the World Cup.

“If you were to understand the economics of stadiums, you would say that they need to be first considered a brewery then afterwards a stadium because that is where your best margin business is, selling beer,” says McKee. For security reasons, the ban on alcohol sales is now back and it removes a huge opportunity for operators of sports stadiums in Brazil.

Despite studies which project that Brasilia will have one of the lowest uses of a stadium post-World Cup, McKee disagrees with critics and says the right operator will understand the potential. The stadium is set to host one of the biggest games in the Brazilian football league with Rio de Janeiro rivals Botafago and Fluminense playing there on 17 August followed by an international futsal (five-a-side football) match between Brazil and Argentina in September.

“It is funny how the media knocks Brasilia for not having a big team here but the people are hugely into soccer so you can have a stadium that is neutral and you can bring international or other matches here and fill the 70,000 capacity,” says McKee. “The other thing is that you have the highest per capita income in the country and people who are used to spending money on entertainment. Yes it is a big investment but it is the people’s to use and benefit from.”

Whether or not, people would have chosen this investment over other forms of infrastructure or community support is not McKee’s concern or remit: as he says the Copa Verde was not a political plan.

McKee says all twelve of Brazil’s stadiums will achieve LEED certification. For the national stadium, a Platinum level of certification will be reached by December after the installation of the solar system, with the opportunity to achieve a higher points rating by completing all work in early 2015.

“Brasilia is an important venue for the Olympic Games as well as for soccer and this will be a LEED Platinum stadium well before the Olympics,” comments McKee. “The solar system is going in now and once the site work is done, it should put Brasilia at around 89 points on the LEED scale, which would make it the highest rated stadium in the world.”

So while the memories of defeats will subside when Brazil’s stars return from Europe to play their next international match, they can thank people like McKee for achieving a long-lasting benefit from the World Cup.

“You have to remember a FIFA stadium is a shell of a stadium for a temporary operator and has nothing to do with how a building operates in its legacy form,” adds McKee. “But LEED is about legacy and having a building which is going to operate sustainably long term. The market needs to demand that these stadiums are run sustainably.”