Photo: SFpark_Wayfinding_04

Study reveals savings from smart parking

28 December 2015

by Jonathan Andrews

Advocates of smart parking argue that the technology can cut congestion and pollution, reduce stress among drivers, and boost economic activity. Adam Pitt examines a new study on smart parking and whether dynamic pricing could make parking a means to stimulate economic growth.

In less than a decade, there will be an estimated one million on-street smart parking spaces available worldwide, according to a study released by US-based research firm, Navigant Research. This will come as no surprise to those keeping tabs on the quest to embed technology within the fibres of the cities of the future. The study also reveals that drivers searching for parking are estimated to be responsible for around 30 percent of inner-city congestion in any given built environment, meaning that making parking more user-friendly is likely to bring about benefits that extend beyond merely reducing any frustrations that exist among urban road users.

“It’s a really compelling technology though the biggest surprise has perhaps been how much slower growth has occurred than what we originally expected,” says Ryan Citron, one of the researchers behind the study. “The last report we put together was in 2013, but growth hasn’t materialised so fast.”

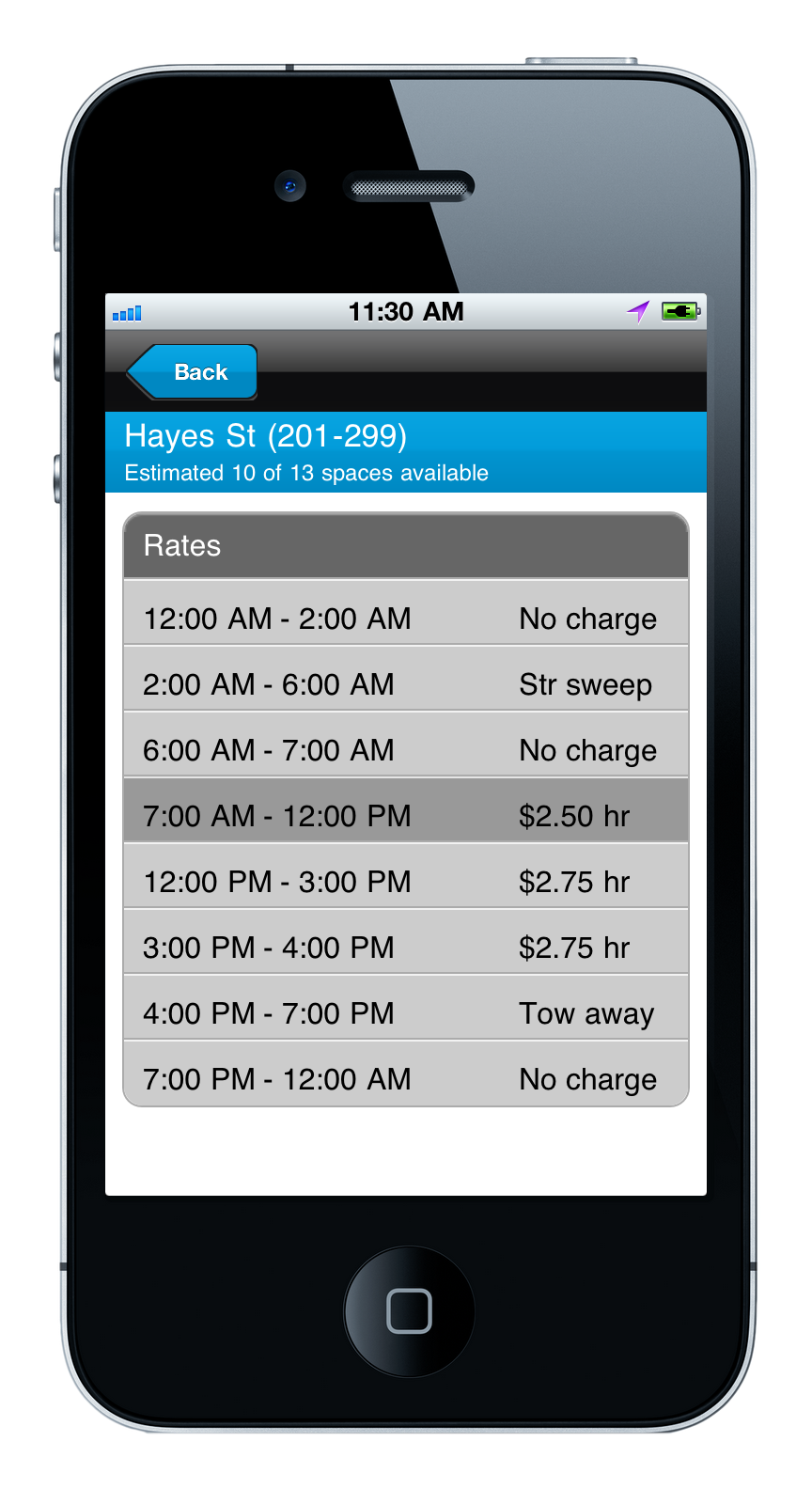

Smart parking uses remote sensors and wireless communications to monitor available parking spaces and relay information to drivers via mobile devices. The potential to reduce congestion and carbon emissions, increase economic activity and productivity, generate higher revenue for local governments from parking fees, and provide a better service for drivers, has inspired trials in some of the world’s most dynamic cities, including San Francisco, São Paulo, Moscow, Copenhagen, Madrid, London, and Nice.

The latter has installed smart technologies in 8,500 on-street spaces and 19 multi-storey car parks and authorities in the French city have reported a 30 percent saving in operational costs and a 10 percent reduction in pollution and congestion. Another study, released by SFpark, found smart parking in San Francisco to have cut the time drivers spend searching for a space by 43 percent.

It is not only big cities that are buying into the idea. Trials are underway in medium-sized cities like Milton Keynes in the United Kingdom, and a pilot is planned for Canberra, Australia in this year. “Smart parking is about enhancing our city centres and making it easier for visitors to drive and park in our cities,” explains Andrew Barr, Chief Minister of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) that administers the city of Canberra. “We wanted a solution that is tailored and that works for the ACT community, because if our city is easier to get around, it’s easier to do business.”

The Canberra pilot has passed the procurement phase and will go live in March or April. It is seen as being a crucial component of the ‘Digital Canberra Action Plan 2014-18’, which is designed to reflect a commitment to creating a technologically smarter city founded on digital services.

“The Smart Parking trial is an example of the ACT Government’s commitment to better transport in Canberra,” says Barr. “In the last few months we have welcomed ridesharing to the capital, an Australian first, and announced the creation of Transport Canberra, a single agency responsible for the integration of buses with the new light rail network. These initiatives, along with Manuka’s Smart Parking trial, will help manage Canberra’s growth, by reducing congestion, protecting our liveability and maintaining Canberra as the world’s most liveable city.”

Finding the funding

However, while projects like those in Canberra may represent an important evolution among urban planners seeking more sustainable methods of growing cities, one important requirement across all smart parking trials is the presence of government funding.

“Systems have proven to reduce congestion, but they’ve had trouble getting off the ground without significant government support,” says Citron. “Take Los Angeles, for example, which received US$15 million from the US Department of Transportation and a further US$3.5 million from the city of Los Angeles. In San Francisco, 80 percent of funds came from the US Department of Transportation and the rest from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.”

In addition, trials in Canberra are set to benefit from a grant of AUD400,000 (US$310,000), as well as additional funding for the operation of smart parking facilities, in part due to the high upfront costs associated with installation and the uncertainty surrounding return on investment. This typically involves factoring in all revenue that is either saved or created through decreased congestion, which is often difficult to quantify.

Despite this, there are those who remain extremely optimistic about what the future holds for smart parking. One of them is Daniel Chatman, Associate Professor of City and Regional Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, who says that while current monitoring methods are costly, the industry is in the process of exploring new technologies and business models that are capable of allowing the industry to become more self-reliant.

“Trials in San Francisco came to an end in 2014 and since then they’ve been trying to figure out how to carry the Project forward under their own auspices, rather than relying on federal funding,” comments Chatman. “That conversation is underway and it’s quite likely that they’ll continue with a less expensive technology, because the sensors they’ve placed under parking spaces are expensive and have a limited life cycle, which obviously increases costs.”

As well as the high cost of sensors installed in the ground, Citron says that the first big project in San Francisco had a lot of problems early on with sensors not being very accurate. As an alternative, the Navigant Research study highlights camera-based detection systems.

“A camera-based system requires only a few cameras to monitor occupancy, thus removing the need to bury far more expensive sensors in the ground,” says Citron, though he believes this technology is more appropriate for off-street parking.

Chatman says dynamic pricing for parking can bring benefits to local governments with prices that increase during peak hours. This, according to Chatman, involves a thorough look at data and an assumption that people are accurately paying, which he says is a problem. But in doing so, Chatman believes one outcome may be increased turnover as higher costs encourage people to park for a much shorter time. In theory, smart parking could become a great economic leveller.

“The way to think about it is that you’re not altering capacity,” says Chatman. “Instead, what you’re doing is reducing the time people idle away looking for parking. If you get pricing right, you’re allocating spaces to people who value them the most and who are willing to pay. Now that can have a positive economic impact if people parking in an area are higher value users that spend more money on retail, for example.”

On the other hand, as Chatman points out, this could actually lead to the segregation of users in a neighbourhood, in much the same way as rent operates in the property markets.

“If there is a pre-market for rent then there’ll probably be a so-called highest and a best use for it, and that area will end up being in a higher rent location than if there weren’t the possibility of charging rent at all and if it was simple a case of whoever gets there first gets to use it,” adds Chatman. “That’s how on-street parking works. So, the economic benefits of smart parking could have an opposite effect. It depends entirely on who ends up using the spaces and for what.”

There is one development that has the potential to make all these theories redundant. As tech and auto giants like Google and Audi lend their weight to the development of commercially viable self-drive vehicles, the question is raised whether they may spell the end of smart parking before it gets going.

“I’m convinced that self-driving car are going to occur. The only question is the regulatory response to them, and how quickly they be incorporated,” says Chatman. “Then the question is whether parking is needed at all–the critical thing about these technologies is that once you get dropped off, your car no longer needs to be there taking up valuable space. It can drive home or go somewhere else.”

Better yet, for mayors who are focused on trying to make cities more sustainable, these cars may not be owned by anyone if they prove cheaper to lease.

“If that’s the case then it’s off doing another trip and that for me would be the best scenario,” says Chatman.

More research on financing and economic impact is needed before smart parking initiatives can be scaled up, especially given that most countries have strict laws against using mobile devices while driving. For now, and with 1.2 billion motor vehicles in use worldwide, it is one option to assist city planners while residents continue to shun public transport in favour of their own vehicle.