Photo: Screen-Shot-2016-03-07-at-10.46.35

Isabel Dedring steps down as London’s Deputy Mayor for Transport

08 March 2016

by Steve Hoare

Isabel Dedring, Deputy Mayor for Transport at the Greater London Authority and the Deputy Chair of Transport for London, describes her role as the “best job ever” but will leave office to join consultancy firm Arup on 21 March. Steve Hoare spoke to her about the move from the London Mayor’s office to the private sector and the challenges facing her successor.

Given her previous stints at Ernst & Young and McKinsey, Isabel Dedring’s move to become Global Transport Leader at engineering consultancy Arup will not be a huge culture shock.

“In the US it’s much more common for people to move between the public and private sectors,” she explains. “It’s healthy. It’s good. It should happen more often.”

A New Yorker who has made what London’s mayor, Boris Johnson, called “a colossal contribution to our city”, Dedring will now take on the task of applying her 12 years of public sector experience to the benefit of cities globally.

Dedring says her new employer’s ethic is aligned with her current role as deputy mayor and believes that who you work with is as important as what you’re working on.

“People who work in the public sector tend to want to do something that’s not just interesting but meaningful for society. That’s very congruent with Arup’s values and they’re known for that.”

With elections for a new mayor coming at the beginning of May, Dedring was happy to provide Cities Today with a snapshot of where the current administration leaves London’s transport infrastructure.

London’s transport challenges

The new mayor–be it Sadiq Khan or Zac Goldsmith–will have to tackle London’s two biggest transport issues: an ageing and capacity limited underground railway network and the capital’s congestion problem. At the same time, he will preside over the launch of multi-billion pound projects such as Crossrail 1 and 2, the Northern Line extension for the London Underground, and several proposed car tunnels.

One of Dedring’s biggest contributions to London’s traffic policy has been the application of a new Land Value Tax (LVT) in such projects.

Dedring explains: “Pretty much any infrastructure project delivers increases in land value around it. The tragedy is that there are hundreds of transport projects around the world–probably thousands–that are being delivered at the moment that do not capture any of that value. It all goes into the pockets of the landowners, which is great for them but it’s all at the expense of–typically–the taxpayer and/or the fare payer.”

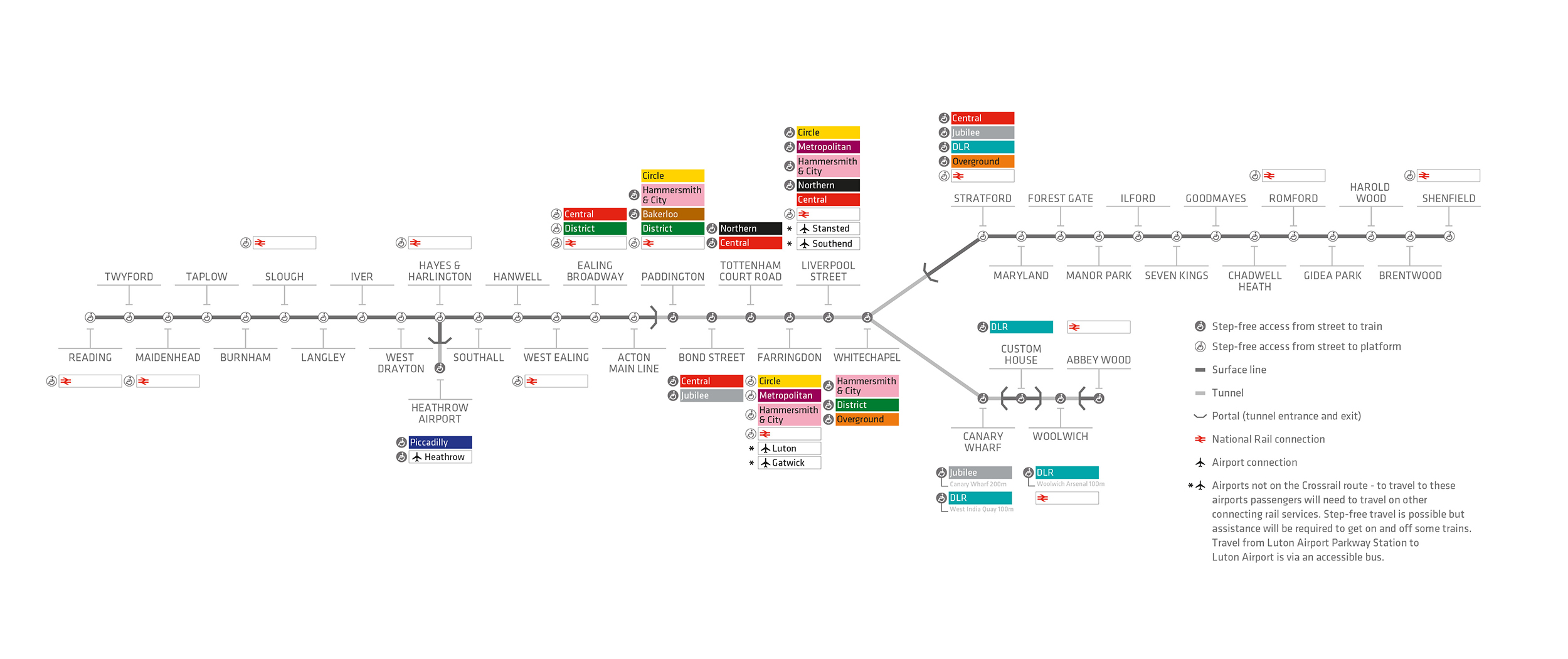

London used LVT to partially fund, along with fares and a government grant, the £15 billion Crossrail project, which will install a new 118-kilometre railway line from the west of London in Berkshire through the centre of the city to Essex in the east.

Businesses within a certain area were charged a supplementary tax of £0.02 per pound to create £4 billion for the project, nearly as much as the government is providing.

The LVT scheme is also being used to partially finance the London Underground’s Northern Line extension but Dedring says it could and should be applied to a whole range of other projects, including the likes of Crossrail 2 and the Piccadilly Underground Line extension.

“We’re still not capturing land value systematically on every project,” she adds. “It needs to be the first source of funding that we look at, alongside fares. Public grant funding should be the funding of last resort. We’re not even close to where we need to be on this. It’s a global issue, not just a London issue.”

Yet, there is little analytical proof that land values are increased by these large-scale projects. Historically, the data has not been gathered and the deputy mayor says the tools needed to measure the value of land uplift need to be used systematically.

“We all know intuitively that increases in land value result from infrastructure investment, but there’s very patchy evidence because it hasn’t been systematically analysed,” says Dedring.

“We need systematic use of these land value capture tools,” says Dedring. “The major constraint is institutional barriers. We don’t have enough people – both the volume of people and the right people with the right ability to structure these deals.”

Thus far, LVT has only been used on multi-billion pound projects but there is no reason why it could not be used on London’s 30-plus medium-sized £100-300 million projects. But there are just two people working in Transport for London on the development of LVT.

“We just don’t have the machinery to grind out the business models, the funding and the financing,” Dedring continues.

Dedring says that City Hall and Transport for London are in fairly intensive discussions about how to solve the problem. They might do this by hiring a team of bankers or by outsourcing to a bank or consultancy with the skills.

“Solving this problem more systematically will be a decision for the next mayor. It might require some significant institutional changes,” she concludes.

There is a precedent from national government. When Andy Rose was Chief Executive of the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA), he set up an investment division to manage the £25 billion fund it uses to finance new homes in the UK. Senior bankers were seconded from the private sector and a team of 80 finance professionals was established.

“It’s not a lack of funding out there in the world and it’s not a lack of projects,” she adds. “It’s the formulation of those projects into concrete business plans with funding streams that are financially structured. No bank is going to do that for free on the basis that they may or may not win the pitch for the work.”

Dedring explains that the political landscape in London is such that transport infrastructure and housing delivery are inextricably linked.

“The only way you are going to get the increase in homes that is so urgently needed in London is, in part, by getting the financing situation right,” she says.

She uses the example of extending a tramline through south London. The development value could be captured from 20,000 new homes that are built along the line to contribute to the financing of the tram extension.

“For a lot of boroughs it’s not a very popular message because we are all used to the previous state of affairs where government would give them a cheque to build things,” says Dedring. “But it’s not like that anymore. Look at Crossrail 2: nobody is going to give us a cheque for £20 billion.”

Environment and transport links

In between stints working on London’s transport infrastructure, Dedring had a two-and-a-half year spell as the Mayor’s Environment Adviser. A recent study by the International Public Transport Association (UITP), claimed there should be much stronger cooperation between health, environment and transport authorities.

“Everyone thinks there should be closer institutional links [between health, environment and transport], but they don’t really exist in the way you would want to see in practice and just saying there should be closer institutional links is not really that helpful,” says Dedring. “What we need is practical methods through to get these groups working together, rather than ideological statements.”

She points out that in London, the mayor has budgetary responsibility for transport but has no authority over health.

“Interestingly, one of the best ways you can get these different silos to operate more closely together is through political lobbying. For example, in London there is massive political pressure on air pollution but London’s air pollution is far better than many, many cities around the world. But because we have a very aggressive political lobby on it–thank goodness–we are able to do a lot of things to tackle it–including allocating transport funding for health purposes, which is often hard to achieve.”

One of the things her administration has done to tackle air pollution is the introduction of the Ultra Low Emissions Zone. From 2020, all cars, motorcycles, vans, minibuses, buses, coaches and trucks will need to meet ultra low-emission standards or pay an additional charge, when travelling in central London. Some critics have suggested this date should be brought forward.

“You need to give people time,” says Dedring. “For example, look at fleet operators. No matter how much we care about pollution, it would not be reasonable to tell people to replace a fleet of 10,000 vehicles next year. That would put many companies out of business.

“I don’t think most people have realised what a big deal this scheme is. Most vehicles driving in central London today would not be compliant with those standards. This is not a minor adjustment. It is going to be a huge change.”

The zone will be focused on central London. Dedring explains that 50 percent of traffic in inner London is going to or coming from Central London. If you tackle Central London traffic, she says, then automatically you have also tackled 50 percent of the traffic in inner London.

There is also work being done outside central London with the creation of a whole series of car tunnels, which aim to shift traffic underground and allow for a more liveable space above ground. There are east-west tunnels being designed in the north and south while half-a-dozen more are being planned to make the environments around busy routes such as the A13 road in the east or the Hammersmith Flyover in the west more habitable.

Capacity and congestion

Other major issues facing the next mayor include a tube network that is fast approaching capacity and a railway network that needs to be radically upgraded and brought into proper rapid transit use.

“There are practically no ‘turn up and go’ rail services south of the river and that needs to be completely transformed,” says Dedring.

To help this, and in a sign of growing devolution of powers for London, the Minister for Transport, Patrick McLoughlin, announced in January that responsibility for railway services to London would be handed to the city government.

On the roads, Dedring advocates a radical shift in terms of tackling congestion.

“I think the next mayor needs to look at how we pay for road use in London. Increasingly, people are saying they are prepared to pay for the using the roads in London if they can have much lower congestion and cleaner air.”

As an example, she suggests vehicle excise duty and fuel duty could be replaced by a distance-travelled charge, which could be a variable based on charging more in central London and less or for free with a clean car.

Dedring believes that the time has come for the rollout of clean transport technologies across the globe. In London, she says the political will is there but the limiting factor is the technology. Some of the shorter routes have been converted to electric buses but the battery technology is not up-to-scratch for longer routes.

“In 10 years time, every single bus in the world should be zero emission. We should not be conceiving of a world where we will have cities that have anything other than zero emission vehicles. It’s just a case of time and political bravery. The technology is more or less there so there are no excuses any more.”