Photo: Tom Wang | Dreamstime.com

Four strategies to transform public spaces for extreme heat

03 August 2021

By: Adam Freed, Lauren Racusin and Jacob Koch, Bloomberg Associates’ Sustainability team of experts

The coinciding crises of extreme weather events supercharged by climate change and COVID-19 have fundamentally shifted how we live, work, interact, and think about our surrounding environment. The past year showed the importance of public space in cities as people spilled out of their homes to reclaim streets, sidewalks, parks, and plazas. The past few weeks have demonstrated the health risks associated with the new norm of extreme weather, with record-breaking heat waves in the United States and Europe overheating cities.

To help cities around the world enhance outdoor areas to protect vulnerable residents, provide access to open spaces, and cool neighbourhoods, Bloomberg Associates, a philanthropic consulting firm for cities, developed a new resource illustrating how to improve the quality of public spaces and reduce the impact of heat waves in social housing.

Below is a look at four strategies to accelerate the transformation of public space for extreme heat.

- Recognise green space as critical infrastructure

The COVID-19 pandemic drew a lot of attention to the design of public spaces and the lack of green areas in many urban communities – particularly neighbourhoods with high concentrations of residents vulnerable to health risks and climate events. Many essential workers live in neighbourhoods without access to infrastructure like parks and open space, which have important environmental and health benefits.

Green spaces within cities can serve as urban oases that provide crucial relief for vulnerable residents. In addition to providing recreation opportunities, they provide shade and lower air temperatures, filter air pollution, and can help reduce flooding. It’s critical that cities have accessible, cool outdoor spaces that allow people to escape the heat within their homes and can help meet the reduced capacities of indoor cooling centres with social distancing restrictions.

Despite the importance of green spaces in cities, a recent analysis by American Forests found that neighbourhoods in the US with majority people of colour have, on average, 33 percent less tree canopy than majority-white communities. Recognising the need to address these disparities and the importance of green spaces, 31 cities have signed the Urban Nature Declaration and pledged to ensure that 30 percent to 40 percent of their cities are green space or permeable surfaces by 2030; or that 70 percent of their residents can walk or bike to a park or water feature within 15 minutes.

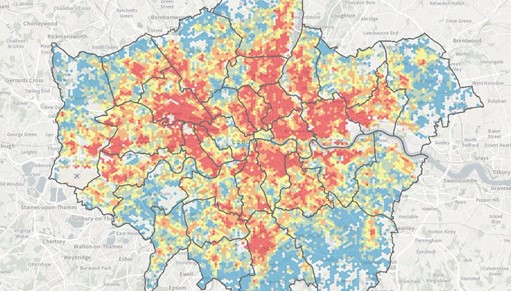

- Take a data-driven approach

While cites across the globe are grappling with extreme heat, the impacts are not universally felt. Within cities, temperatures can vary up to 20°F depending on the layout and design of communities. In many cases, these disparities are a result of historically racist policies and deliberate design choices that left lower-income neighborhoods with more dark asphalt, fewer trees, and less green spaces. The Trust for Public Land estimates that 100 million people in the US, including 28 million kids, don’t have a park within a ten-minute walk of their home. Faced with limited resources and uneven risks, data can help municipalities understand where the greatest opportunities and needs exist.

In Milan, Paris, and London, Bloomberg Associates developed climate risk maps using satellite-derived land surface temperature, demographic data, and information on urban form. This helped decision-makers understand which neighbourhoods were more exposed to extreme heat and had higher concentrations of populations vulnerable to climate risks (such as seniors or low-income households). The data allows cities to target cooling interventions, such as tree planting, depaving, or the opening of “cool spaces” in neighbourhoods with the highest risks.

- Creatively leverage all public spaces

Space is always at a premium in cities – whether it be for affordable housing, economic development, or parks. Cities need to build on their creative thinking during the pandemic to leverage all public assets beyond traditional parks that can be used for open spaces and cooling their residents.

In response to the growing demand during the pandemic, many cities closed streets to cars, replaced parking areas with “streeteries,” erected temporary bike lanes, and created pop-up play spaces and plazas. Cities need to keep this momentum and move this revolution of public space beyond the streets to other areas.

Utilising public space or publicly owned assets beyond parks and streets — such as social housing sites and schoolyards — can enable cities to reduce the impact of climate change and provide much-needed open space and greenery. For example, Milan is rethinking the open areas that are part of its publicly owned social housing developments, which are home to eight percent of the city’s population, to provide more outdoor cool spaces and recreation opportunities for residents. Paris is transforming its 700 schoolyards into “Urban Oases” to provide cool refuges for residents during hot days. This includes incorporating trees, shade structures, light-coloured pavement, and sustainable stormwater management practices to targeted schoolyards and opening them to the public on hot days.

- Design spaces to be cool

In many cases, design choices are heating up neighbourhoods together with climate change. Dark asphalt, lack of trees, and poor air circulation can raise surface and air temperatures. In Bloomberg Associates’ 2019 Mitigating Urban Heat Island Effects: Cool Pavement Interventions report, we identified multiple interventions such as incorporating trees, greenery, light-coloured surfaces (such as roofs and pavement), and water features that can help cool outdoor areas and provide refuges to residents.

In Milan, we are working with Mayor Beppe Sala and MM Casa, the quasi-public agency that manages most of the city’s social housing, to make outdoor public spaces at social housing sites in the hottest parts of the city cooler and greener. This includes planting new trees, providing new seating and tables in shaded areas, adding public art, and providing play areas for children.

Equitable access to quality green spaces and risks to human health are interconnected issues that are often overlooked in cities, but the pandemic has brought these issues to the forefront of urban planning. In terms of public health, there is increasing evidence that race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status affect a person’s risk for COVID-19. In parallel there is evidence showing how vulnerable communities have been disproportionately impacted by long-standing systemic inequities such as social, environmental and health policies.

COVID-19 and the past few weeks of extreme heat have shown that these spaces are not simply an amenity, but part of a city’s critical infrastructure. As we recover from the pandemic, cities need to rethink how to design open spaces to build healthier, more inclusive communities that can withstand extreme temperatures.

Image: | Dreamstime.com