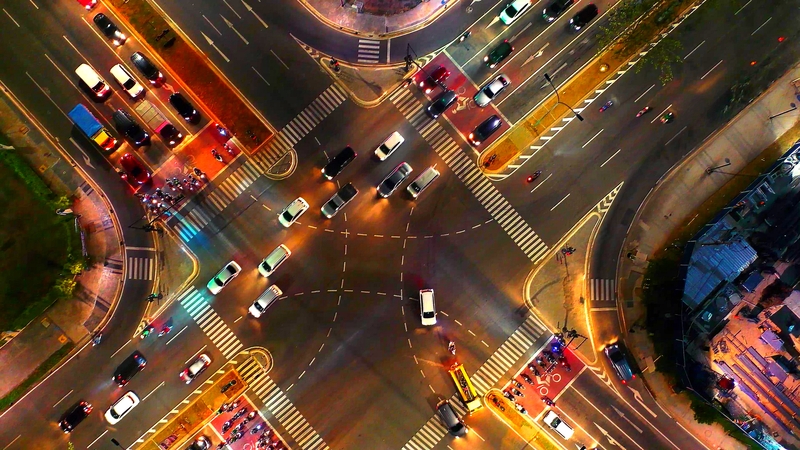

Photo: Pojoslaw | Dreamstime.com

Addressing unequal access to safety in cities

09 June 2021

By: Michael Lake, President and CEO of Leading Cities; Shagun Sethi, consultant for Corporate Social Responsibility at Grant Thornton and a Leading Cities Research Fellow; and Juliana Vélez-Duque, a consultant for Sustainability, Resilience and Climate Change at conTREEbute, advisor to the municipality of Apartadó, Colombia, and Research Fellow at Leading Cities.

Mary Lathrap’s poem eventually titled Walk a Mile in His Moccasins, written in1895, reminds us to appreciate the experiences and challenges others face in their daily lives. To better understand the perception of safety in cities, we ask you to now ‘Walk with Women’ and seek to understand the daily hardships created by the inherent gender bias in urban design.

Safety is a privilege, safety is a feeling, safety is freedom; and yet it is one which is not shared equally. Women and minorities more often operate with a sense of insecurity and feelings of being unsafe while in cities, and this hampers their psychological, social, functional, and economic progress and wellbeing.

Today, safety is narrowly examined by looking at crime that has taken place in the past – areas with high rates of crime are deemed unsafe whereas a low crime rate suggests safety. The loophole in this approach is the lack of acknowledgement of the psychological aspect of safety – an understanding of what makes people feel safe is the key part in ensuring a safe environment.

Cities have historically been designed, occupied and dominated by men. Considering the predominantly male gaze and presence in urban planning, it is fair to say, however unintentional, that cities have been constructed by men, for men. The masculine nature of urban space does not account for systemic violence against women, and the subsequent threat of harm and fear with which they operate. It does not include elements of design that invoke feelings of safety and security. Women’s experiences in cities are hence dictated by physical manifestations of patriarchy, in the form of laws, urban settings and design elements. This goes to show that women are afraid of accessing the city, not because they are delicate and fragile individuals, but rather as a result of a systemic issue that reinforces violence against them because of their gender.

Mapping

In our research, Walk With Women – Gendered Perceptions of Safety in Urban Spaces, we attempt to understand how people perceive fear and safety in urban environments, specifically when walking through the city, and how this can be affected by gender and by elements of urban design.

Our research has found shocking statistical proof of our hypothesis that women operate with a heightened state of alertness and that they alter their behavior due to a fear of gender-based violence.

We gathered results from 12 countries and found that not one man studied noted sexual assault as their biggest fear in accessing cities. In contrast, over 70 percent of female respondents noted sexual assault as their biggest fear. Around 70 percent of the surveyed men said they ‘never’ or ‘very rarely’ avoided walking in the city because of fear. On the other hand, almost 70 percent women ‘occasionally’ or ‘very frequently’ avoided accessing cities by walking due to the consistent fear of violence and sexual assault. Cities evidently are not the safe haven of opportunities and inclusion for all that they promise to be.

To address these problems, and the lack of connection between psychological states of operation and on-the-ground measures of ensuring safety, we provide recommendations for policy makers, urban designers, architects, industrialists and citizens alike. An encouraging result of our research is that men and women perceive elements of urban design in similar ways, and while men would not alter their behavior in the absence of these elements, they would still prefer cities which have these amenities (street lights, active store fronts and so on) – this means that by designing safer cities for women, we also design safer cities for all.

For this global, amorphous problem, the solutions also need to be global and all encompassing. We need women and minorities to be a part of decision-making processes and their voices to be heard in all phases of the planning process – the deliberation, policy formulation and implementation.

As part of our recommendations, we note that a clear stakeholder mapping exercise is necessary to understand and map those who are affected by the problem, those who participate in decision-making and those who are at the forefront of bringing change and advocacy.

We also recommend a thorough mapping of the community, whether it is a corporate office, a university, or a city, be done to understand the demographics and subsequently the needs and problems of those that are to benefit from change.

In line with the mapping exercise, a very effective tool is to create two maps of the city – one that is seen from a male perspective and the other from a female perspective (this should be done for all genders and sexualities). These maps should depict the differences in the ways men and women view cities. Then black out the areas that women do not access/use due to concerns of safety (quite literally use a black marker and cancel out these areas/streets on the map that is created). When compared, we predict that you would have two maps in front of you, and that the map created from women’s perspective(s) would have many areas blacked out – this is both important and saddening.

Urgent action should be taken to ensure that the whole city is accessible to women and other genders.

Walk the talk

Our report includes other action items which could help increase the access women have to cities and enable a gender-centric approach to the urban design and public policy aspects of planning. Activating the night, creating ‘centres of service’ and deep dives into problems faced by women, are some of the major recommendations we explore in the paper.

Space does not have individual agency, its meaning and power is determined by those who use and own that space, and unfortunately, today this meaning is predominantly masculine in nature. With our research, we hope to redefine the relationship between the different genders and urban spaces to create truly ‘public’ spaces, equally enjoyed and experienced by all.

Image: Pojoslaw | Dreamstime.com