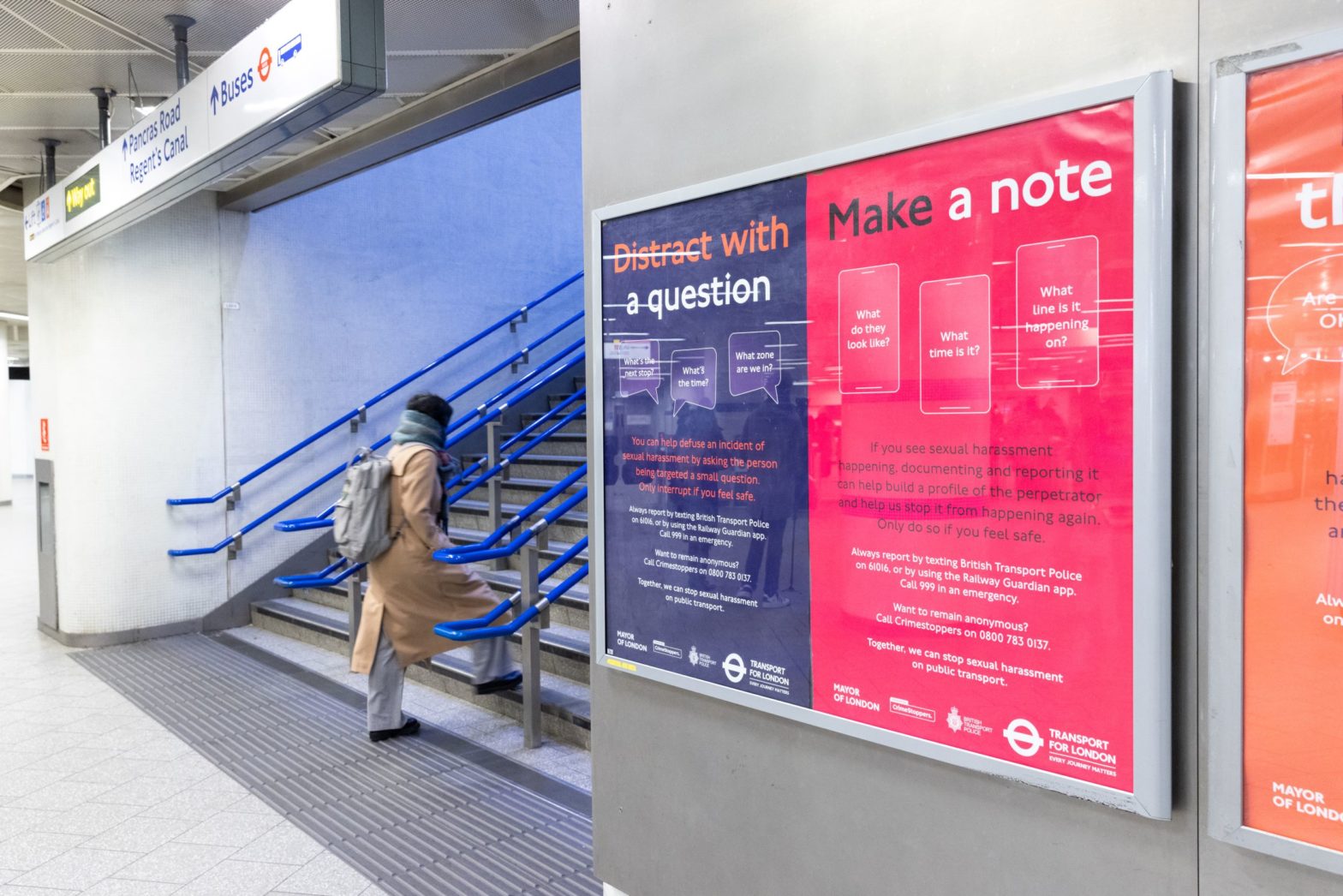

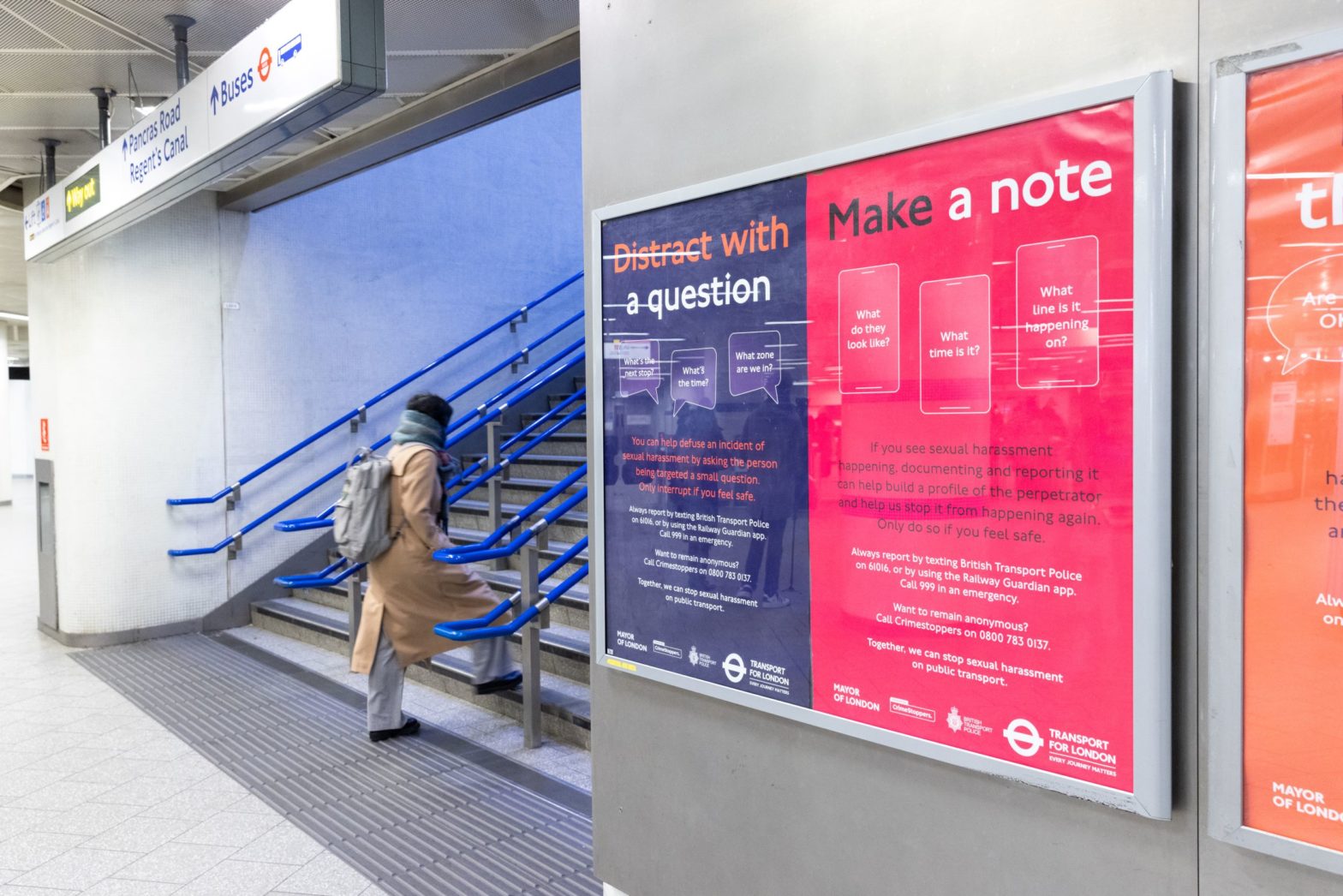

Photo: tfl 3

How London is trying to make public transport safer for women

02 March 2023

by Christopher Carey

Photo: tfl 3

02 March 2023

by Christopher Carey

As passenger figures inch back towards pre-pandemic levels, a growing number of cities are re-examining how they can make public transport safer and more inclusive.

Reports of attacks and anti-social behaviour directed at staff and passengers have been on the rise globally over the past two decades, with an August 2022 study by the Mineta Transportation Institute finding the trend is “a relatively recent phenomenon”.

While developing cities, especially in South Asia, continue to account for the most serious attacks, countries with advanced economies are reporting a growing number of incidents.

Women in particular have reported feeling increasingly unsafe on public transport, and are...

Unregistered users have limited access to our stories. Register for free now to enjoy Cities Today without restrictions.

Already a subscriber?

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

You have reached the limit for the basic subscription. Please upgrade to Premium to download more

You have reached the limit for the basic subscription. Please upgrade to Premium to save more