Photo: Screen-Shot-2018-09-24-at-10.28.30

How African cities can play to win

24 September 2018

by Jonathan Andrews

A new report highlights what African cities and governments can do to increase their share of foreign direct investment. By Jack Aldane

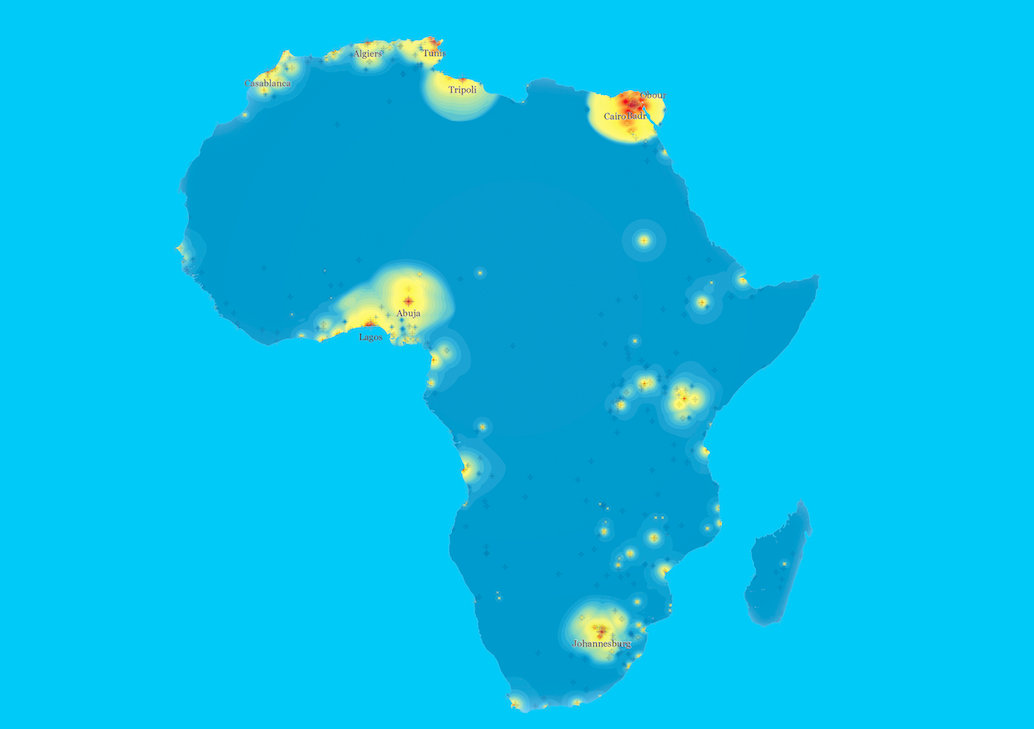

In Africa, cities hold the key to the future of the continent. Africa’s urban population is set to triple between now and 2050, but in order to compete in and connect with the world economy, its governments need to attract more foreign direct investment (FDI).

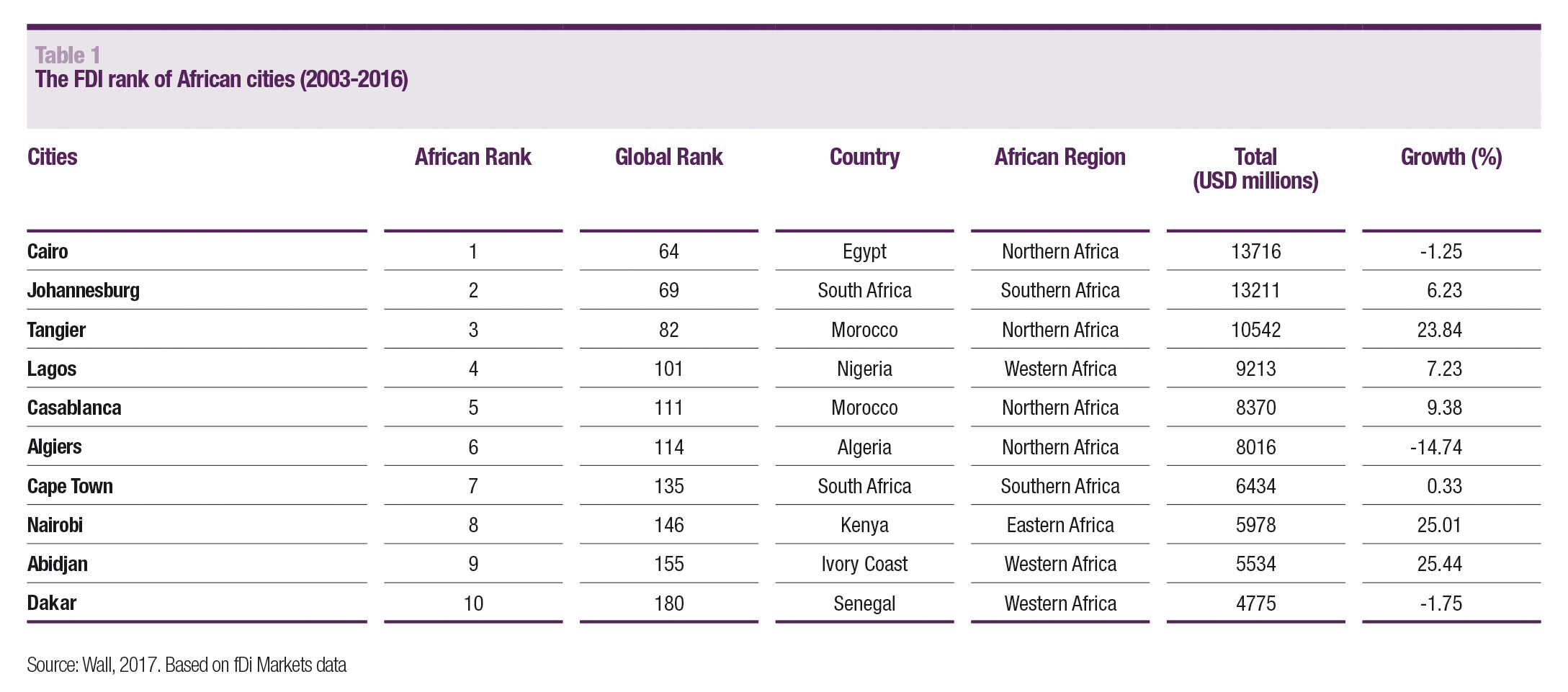

UN-Habitat, the Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies at Erasmus University Rotterdam (IHS), the University of the Witwatersrand and the African Development Bank (AfDB) have teamed up in the State of African Cities 2018 report to reveal what attracts FDI to cities and to provide practical guidance to policymakers on what could improve the economic attractiveness of the continent. According to Professor Ronald Wall of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and Erasmus University Rotterdam, who is the lead researcher and author of the report, the problem is that Africa remains “disconnected from the FDI backbone of the world”, attracting just 5 percent of global foreign direct investment. In Africa, Cairo ranks first in attracting FDI, yet globally it ranks 64th (see table 1).

Networking for cities

The relationship of cities to global investors mirrors that of citizens to their cities. People come to cities offering skills and in return expect education, social mobility, employment, entertainment and culture. Cities offer the world sectors that produce goods and services, and in return seek investment and trading partners. Like people, cities gain an advantage by being multi-skilled and by making connections with each other.

Wall explains that the investment linkages taking place between cities are just as important as the those taking place within them, and both determine their economic power. The more other cities a city is connected to, the higher the value of inward investment it is able to attract.

“Everyone is concerned with making cities smarter or more attractive within their own borders, but in a globalising world, you have to develop the diversity of investment connectivity to other cities,” he says.

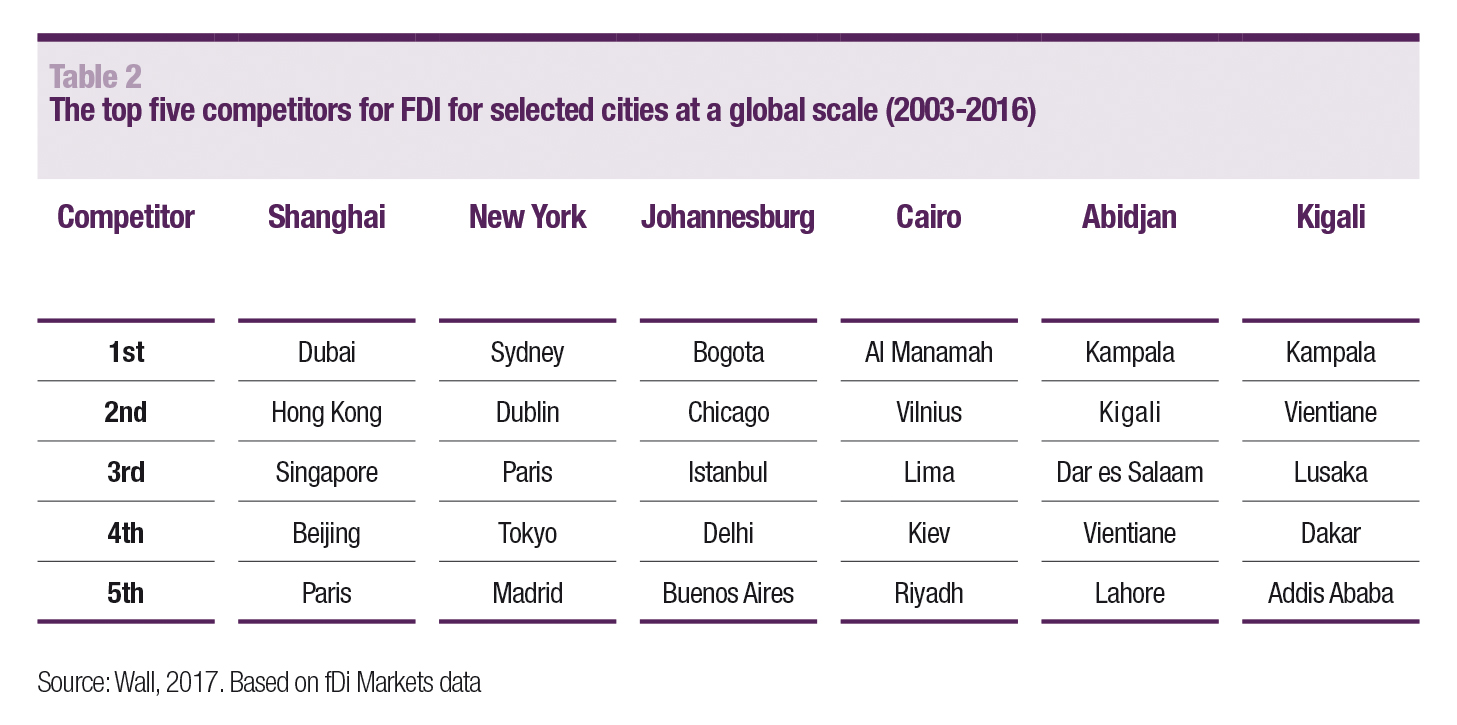

Global competition for investment is intensifying, and as the report makes clear, this is not only increasing the level of competition between cities in Africa but also with other cities which investors see as alternative locations. Most cities attract investment into the same sectors, making them easily replaceable, and hence strong competitors of each other. It is therefore important that cities specialise and diversify their FDI sectors, which will reduce the level of competition.

One of the key achievements of the report is to help African cities identify who their real competitors, allowing them to come up with marketing and structural policies to differentiate themselves.

“Every city has to understand what its role is within the global investment network. Once you have that knowledge, you can create very specified policies, stealth policies if you will,” explains Wall.

If a city attracts the same volume of FDI in the same industrial sectors as another city, then, to investors, these cities will be seen as perfect substitutes for each other. This calculation of competitiveness between cities is referred to as the Manhattan Distance Model. Examples of cities which are direct and close competitors are Johannesburg and Bogota, or Cairo and Al Manamah (see table 2). Although they are in different regions, these pairs of cities are seen as ‘true global competitors’ with respect to each other. The report also highlights the regional competitors for different cities.

To attract more investment, the report recommends that African cities focus on regional diversification while diversifying their own portfolios. The better the mix of FDI sectors, the more FDI will ultimately come their way.

Wall says the level of diversification among African cities remains “pretty weak” compared with cities globally. Shanghai has by far the most highly diversified and value-added portfolio of any city in the world, yet because its sectors are so different to those of New York, they are in fact not close competitors.

The trick for African cities such as Cairo that may want to, for instance, attract more biotech FDI is to look at which global cities perform best in that sector and determine the social, spatial and economic factors that attract this type of FDI. Based on this strategic knowledge, Cairo would then be able to develop policy and planning tools to better compete for this type of foreign direct investment.

Africa first

For any continent, it is important that cities can connect to other cities. For Africa, it is important that cities are connected by something bigger, something that builds their economies from within the African border. Wall says that this means establishing an ambitious policy initiative in which Africa puts Africa first.

“It needs a continental plan, a pan-African policy at the African Union level. Then there should be regional level policies, e.g. ECOWAS and SADC [regional economic groupings in Africa], down to national then municipal policies”, he says.

Sebastian Kriticos, a city economist for the International Growth Centre (IGC) and participant in the Cities That Work programme, says a city that provides an attractive environment for multinational businesses requires “active policies to provide the infrastructure, markets, and skills necessary to lower production costs and encourage firms to invest”.

Data is fundamental to building reflective policies of the kind Wall and Kriticos reference. The UN has urged that more be done to gather data, but as Wall and his team discovered, the lack of data particularly at the city level makes it arduous work to compile insightful reports. He says it is crucial that African researchers be put in charge of the process.

“Its important to collaborate on data and research, but African researchers need to increasingly become masters of their own continent and destiny, because today there is a form of research colonisation taking place in Africa by powerful non-African institutions”, comments Wall.

The rules of attraction

As demonstrated in the report, its not all good news on investment: FDI can exacerbate social inequality and lead to environmental destruction. The future of the world depends on just the opposite outcome: a wider and more inclusive distribution of wealth across populations that live in sustainable environments and that have knowledge of and respect for the planet. If those populations are to reside in cities, then those cities need to attract sustainable types of investment.

Attracting the right sort of firms is therefore vital once a city gets to know its strengths and true competitors. Only through informed planning and policymaking can countries and cities create collaboration between firms and markets.

Wall says the report finds many African cities simply lack the technological absorptive capacity and institutional reliability needed to lay the groundwork for investment. Those that do attract investment often attract the kind that increases rather than decreases inequality. Yet, it’s important the continent realises that it can’t keep blaming multinationals.

“It should be the mission of governments to make powerful regulatory investment attraction policies that set the conditions for investors, in the interest of ensuring inclusive growth in cities and the protection of Africa’s cultural and natural heritage”, says Wall.

Marketing is important if a city wants to attract FDI. Stefan Atchia, transport policy specialist at the African Development Bank (AfDB), which co-funded the report, recalls an ex-minister of finance of Mauritius warning that the country was “not the only pretty girl in town”. Other countries such as Vietnam, Pakistan, Thailand and Bangladesh, had also put on their best appearance to attract investments using fiscal incentives, fast-track business licensing, ease of work permits, visa facilitation and low-tax policies. Wall says investment promotion agencies can help get a city pitch to the right audience.

Big-tech

It has been said that data-driven technology will help cities in developing economies to make rapid jumps in terms of how they deliver municipal services, and firms such as Google and Facebook have made no secret of their ambitions for Africa.

To have these companies make significant moves on the continent could be a good thing, Atchia says, provided they can help smaller businesses grow and assist a municipality with its managerial tasks. Some cities have yet to reform their management processes, such as systems of municipal taxation and land tenure while others, such as Kigali, have made significant progress. With good systems in place, big tech can provide useful platforms for entrepreneurs to build their applications and improve the efficiency of the services in a city. He uses Abidjan and Nairobi as contrast examples of rideshare adoption.

“In Abidjan, Uber is not present, and ‘car for hire’ services using smartphones are struggling to emerge. In Nairobi, however, Uber is present, and many local firms are now mimicking Uber, introducing strong competition on mobile platforms.”

For Kriticos, penetration of big tech raises concerns over the balance of the urban system in Africa. He says national governments should try to attract FDI to places outside major cities to create jobs across a whole economy. Over the course of development, Kriticos adds, large cities tend to specialise in high-value, tradable technology industries, while manufacturing decentralises towards secondary and tertiary cities. Relying on Africa’s ability to leapfrog traditional industries may be an unwise strategy.

“Given the fact Africa is yet to develop a strong manufacturing base, attempting to jump the hurdle into high-tech services could challenge the development of smaller cities,” he says.

Skills and wages

Average wages in Africa are making its cities dramatically less competitive. They are so low in fact, that Wall says investors rarely factor them into operational costs.

This indicates why, as leading African policy expert Paul Collier has explained, many of Africa’s national governments prefer to keep young people at arm’s length from cities where they are more likely to riot against firms that pay poorly than comprise a world-beating workforce. As a result, youth unemployment in Africa is a staggering 60 percent.

Wall says policy is critical to establish a minimum wage across the continent: “Otherwise, firms will simply go to a neighbouring country.”

Capacity building is a key challenge for cities to attract FDI and needs to be tackled alongside new policies and investment laws. Atchia adds that African cities that successfully attract global finance “have a significant pool of local bilingual professionals such as accountants, engineers, and lawyers to back up your business”. The question is whether more cities can provide such resources or if those flocking to cities will just become part of the informal economy, putting more stress on municipal services and failing to advance living standards.

Kriticos says Cities that Work has collaborated with members of the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) to create a Directorate of Revenue Collection (DRC). Technical skills and motivation were provided at the outset of the project. This proved that the city could reliably raise and manage money from a range of local sources and has been a major step towards improving Kampala’s creditworthiness.

“The main lesson that other municipalities can learn from this is that for reforms to be effective, a well-trained workforce is essential,” says Kriticos.

Policy and capacity building notwithstanding, Africa holds many trump cards. It is the most resource-rich continent on Earth, and demand for these material and agricultural resources, as well as Africa’s human capital, are only likely to increase between now and 2050.

But without pan-continental regulations, Wall believes “Africa is likely to be exploited all over again”.

China has come in for criticism in this regard, and while the volume of Chinese investments in Africa relative to those bound up in Europe’s historical ties remains relatively mid-tier, its growth rates in Africa have been strikingly high. With new data from Peking University, the report provides some interesting insight into Chinese investment patterns in Africa and the motives behind them. While it is difficult to give a definitive verdict on the motivation of Chinese State- and non-State-Operated Enterprises, far from being just a neo-coloniser of resources, China’s investments seem to be market-oriented within Africa, often in underinvested states in order to avoid competition with advanced economies. China can take credit for stimulating economic development in some African countries, particularly through energy and infrastructure investments. However, the over-reliance on Chinese management and lack of attention to corporate and social responsibility are less positive for long-term development.

Playing to win

The fourth biggest investor in Africa is Africa itself, with cities such as Cairo, Casablanca, Johannesburg, Lagos and Nairobi investing across the continent.

Wall says any city can attract some level of investment, but that only a few have the power to invest in other cities. This is what separates the economically powerful global cities of the world from the rest. Cities placed high on the democratic scale tend to attract more investment, but the policies advocated in the report really serve to flag the need for governments to develop African cities in accordance with their unique capabilities and to connect that to sustainable urban development.

To compete for FDI, African cities must know their strengths, as well as who their competitors are, and must be able to network and sell themselves based on their own merit. Most importantly, these cities of the future need to set boundaries for global investors and decide the common rules by which they can play to win.

To download a free copy, see: cities-today.com/StateOfAfricanCities/