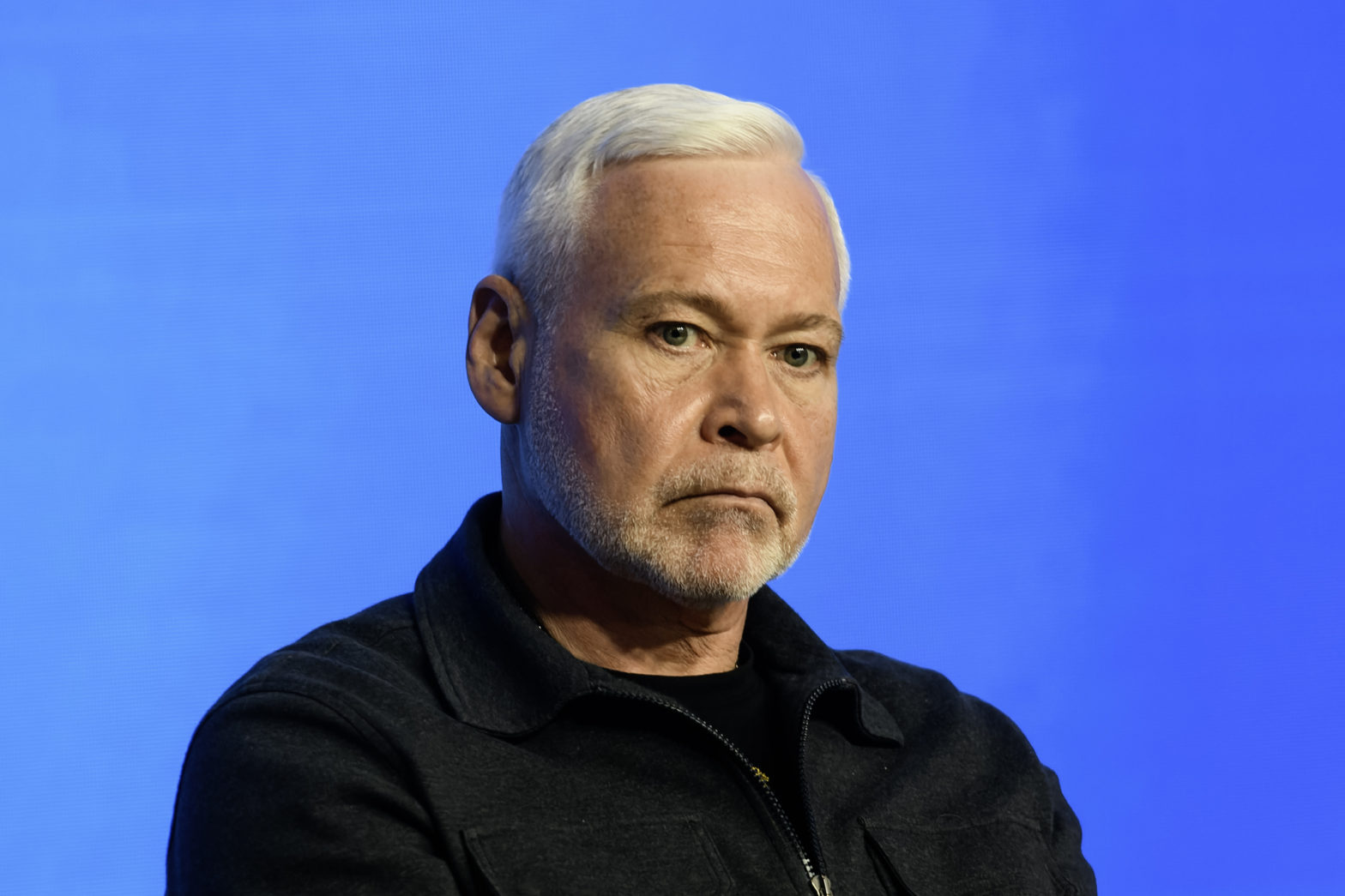

Photo: City-of-Boston-low-res

Government sees bottom line differently to business: Boston’s CIO

28 March 2018

by Jonathan Andrews

Jascha Franklin-Hodge, CIO, City of Boston, stepped down in January after four years driving the city’s digital strategy. Jonathan Andrews spoke to him about his time in office and how the city is working with shared-economy disruptors to provide better digital services for its citizens

You founded a web-based software company in 2003 and then managed it from a start-up to a company with 200 employees. What prompted you to apply to become CIO of Boston in 2014?

Two things: after a decade of building a business I was ready to do something else. The other reason was that I had over time–in large part through some of my advisory work with Code for America–found myself really interested in the challenges facing cities, and how city governments were trying to figure out how to metabolise the technological changes that were transforming every other aspect of life. It was very clear that cities didn’t always have the necessary people, resources or strategic outlook to put that technology to work on behalf of constituents. That struck me as both a very serious challenge and a very worthwhile one to undertake. When I saw that my own hometown was looking for a CIO I jumped at the chance.

How far is Boston in replacing legacy systems with cloud-based and open source systems?

We are making good headway. We still have a fair amount of legacy on-premise infrastructure, but it’s largely things that are relatively easily movable into the cloud. This can be done either by replacing it with Software-as-a-Service applications where there are good solutions that make economic sense, or by moving the underlying infrastructure into the cloud-based environment and taking them off local servers.

As an example, we built the city’s website on top of Druple which is being hosted by Acquia, so using open source and cloud-based service provisions. We are in the midst of migrating our CRM [customer relationship management] system to Salesforce, which is again moving off of an on-premise solution.

As a city we are trying to embrace open source communities, not only as users of open source technologies but also as participants. We’ve open sourced a lot of the work that we have done, including the code for our website. Some of the applications that we’ve built can be useful for other cities and we can engage with civic technology groups in Boston to help us with things that are valuable for the site.

How is the city dealing with vendors and potential partners as part of that process? Tell us about a project you are working on with a vendor.

Vendors play a crucial role in most of the work that we do. Our CRM system is a good example of the model that we are trying to adopt with vendors.

Until now there has been a high degree of vendor dependency. Typically, a city will buy complete solutions from one company with everything fully integrated. You are then essentially locked in to that company’s technologies and if you do want to migrate away it’s a massive re-implementation effort of every part of the system.

Our approach has been to try to procure and build things alongside vendors that allow more flexibility. Rather than buying a full stack solution for everything that is related to CRM and the 311 services we offer, we are buying a Software as a Service, core CRM package but we are working with another vendor to build the mobile application.

We are building a web application in-house that will interface with the CRM system using standard APIs [application programming interface], which gives us flexibility if we ever decide to change one component in the future. It means we are not beholden to trying to find a vendor that can do an amazing job in every part of the system. More often than not, when you hire a vendor that is great at one piece but not in another, you end up making some compromises.

What is one common mistake vendors make when talking to you?

There is a long list of mistakes [laughs]. Trying to offer a complete solution to everything is definitely not a good strategy for organisations like ours which have some substantial in-house technical capacity. We are not just looking for someone else to do it; we are looking for someone to partner with us and build the right solution for our users. Oftentimes, that means mixing and matching the best solutions.

The other big mistake that vendors make—which is especially true in the smart cities space—is that there tends to be an intense focus on efficiency as a selling point: ‘If you do this thing with data you’ll be able to collect the garbage for 20 percent less money’. While efficiency does matter to some extent, in government the bigger animating force is really around quality of service and our ability to deliver for constituents. Unlike a business where ultimately everyone is answering to a bottom line profit number, efficiency gains will typically creep into that bottom line.

In government we are answering to the constituent happiness bottom line. Efficiency gains don’t necessarily translate into constituent happiness, especially if it means that we are changing the way we are delivering a service so that it is less aligned with people’s expectations or people’s feelings of how that should be delivered. The bottom line of government is very different to the bottom line of the private sector and trying to pitch solutions with a private sector bottom-line mentality is a common mistake.

How much of your role is trying to foster economic growth in building a city economy and what role do start-ups and smaller business play in that?

To be honest, very little of my role is focused on that. We have an economic development team that we work with closely. We do try to have an open door for those companies and entrepreneurs in the area that have interesting products and want to partner to pilot something, or to get feedback, so we engage a lot with the start-up community in Boston and engage a lot with researchers and students at local universities that may be working on a start-up idea. A lot of times it’s just to give them feedback; sometimes we’ll do a pilot, sometimes we’ll make city assets available for them to try something out in the real world, but that is really the extent of what we do in terms of economic development.

How do you divide responsibilities in terms of your own office and that of the Office of New Urban Mechanics?

We work very closely with them and both of our organisations play a role engaging with start-up companies. New Urban Mechanics is frequently the place where companies that have a very experimental idea will go to get feedback, engagement and sometimes the opportunity to pilot. Because we are more of an at-scale IT organisation, it can be a better fit for larger organisations or people with a more mature product where it’s actually about trying to implement something on a broader scale. However, we work very closely with them on these kinds of things.

In which area of the so-called smart cites concept do you think Boston is leading?

The things that usually crawl under the smart city umbrella that we do very well include people-focused analytics. This encompasses how we use data to improve quality of life, or to make government service delivery work better. Sometimes that kind of work is not sexy in the way that smart cities are not always about devices and sensors and data but really about how to take the information sources that you have as well as new ones and apply them. How to find an efficiency that actually matters to people, improving the flow of traffic through a neighbourhood, making a road safer, improving the performance of the ambulance service to reducing the amount of time it takes for an ambulance to get on scene when there is a call. Those are the kinds of things that we tend to be very focused on. It is rooted not in a techno-centric view of the world but an outcomes-centric view of how we can improve service delivery.

Which cities do you look to as leaders?

There is some very interesting experimentation being done now in San Diego, Atlanta and New York around the provision of more traditional IoT-type devices. San Diego and Atlanta are doing relatively large deployments of street light sensor kits and video analytic systems. New York has LinkNYC which is a very interesting platform. I don’t know that any of these I would look at as clear-cut success stories, but from what I have seen they have been a good success for the city in terms of revenue. That said, I don’t think you could look at any of these and say, ‘Oh, this has clearly impacted quality of life in a big way for people’, but I think it is still early days. We are excited to follow along on their journey as they try some of these new technologies at scale and as we see what they learn, and the benefits that they hopefully see. There may be opportunities for us to follow suit or to build on the work that they have done and find additional applications here in Boston.

In terms of reaching citizens, or customers as many cities prefer to call them, are 311 services your main source of feedback and interaction? How do you get a good cross-section of society to provide feedback digitally?

Interestingly enough, about a year ago we crossed the mark where the 311 mobile app became the dominant source of data for reports on issues compared to the phone [voice calls]. Right now, digital sources are about 60 percent of the total number of issues that get reported to the city. Increasingly we are looking to the web as a critical interaction point. We have millions of visits per year to the city’s website. I would say that for the majority of our residents, that is going to be the first place to go when they have a question, such as if schools will be open [after bad weather] or if their trash is being picked up that day.

We’ve really tried to focus on building exceptional high-quality digital experiences that deliver a level of service to them. This makes them feel like they don’t have to pick up the phone and they are getting what they need quickly and easily in a way that is friendly and helpful to them.

You have had some experience with Uber and Airbnb and other ‘disruptors’ who are beginning to open up their datasets to cities. Can you give examples of successful business models you are employing or would like to introduce to share data with businesses to provide better city services?

The only successful example of this I would say is with Waze and their connected citizens programme. They’ve been really helpful about sharing information with us about street traffic congestion and road performance. We’ve been able to integrate that into some of our planning efforts. When we go to re-time traffic signals at a given intersection, we can use Waze data to validate that the re-timing has had the desired effect of improving traffic flow. We can also use Waze data to look more broadly at the system and see if changing one signal pushed congestion somewhere else.

We’ve also done a little bit of experimentation of pushing data back out the other way into the Waze application, such as providing Waze with a list of the most dangerous intersections in the city, so that when a driver approaches an intersection that’s had a lot of crashes they get a warning saying that this is a good place to slow down. That has been a positive relationship.

Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb I would describe as works in progress. There is interest on the part of the city in getting access to some of the data that they have, so that we can help manage the roads or housing supply. I think there is a stated willingness on the part of some of these companies to engage with us and share data. That said, we have struggled a little with some of these companies to find the overlap between what is useful to us from a policy-making perspective and what they are comfortable sharing from a proprietary information perspective. Although we have done some data sharing with Uber and a very small amount with Airbnb, we have not really had the chance to get to a place where I can look at either relationship and say that this is really high value for us.

One conversation we are starting to have with Lyft is whether we can get information that allows us to better manage road use for places where there is a lot of interaction between their vehicles and other uses. For example, at a major train station you can have people getting off the train and ordering a Lyft and people getting on the subway. We started to have conversations to work with them to get data that allows us to be stewards of the public space in those areas. I don’t think there is a clear roadmap quite yet for how to make that [relationship] successful.

With the move to 5G–which unlike 4G requires almost line of sight connection to devices and hence the need to put up more mobile masts or utilise streetlights and traffic lights–is this going to be a cash boon for cities? Are you looking at aligning companies with the city’s policy on increasing access to the Internet for all residents?

It will depend a lot on the regulatory environment at the federal level here in the US. There is a move afoot that will severely limit the ability of cities to generate revenue but also to even manage the basics of their public right of way. It is something that we are fighting here in Boston. The revenue is important but also we actually think that an effective city-run management programme is going to be better for the telecommunications companies.

We are very supportive of installing equipment on public rights of way. We have a programme that is very efficient in providing reviews and approvals for applications to install equipment. We typically approve most applications in less than 10 business days, but we also have some really important public policy objectives. We want to protect the aesthetics of our streets, especially in historic areas, and want to make sure that the equipment installed is safe. We want to make sure that we are managing that infrastructure effectively, so it doesn’t interfere with street lighting operations.

We want to make sure that one company can’t come in and buy up all the available infrastructure and use that to prevent any competition. There are some very important and legitimate things that cities need to do to manage this incredibly valuable asset. It’s certainly our hope that by virtue of being able to collect a fair market value for use of this public asset by private companies that it will give us the resources to manage those assets to the public benefit but also to encourage the kind of investment interest that we are seeing.

What was your biggest challenge as CIO?

The biggest challenge that I have had is simply the amount of demand for better technology solutions that exist within the city. When I took the job, I wasn’t sure if I was going to have to be spending a lot of time convincing people why technology can be helpful to them inside of city hall, and quite the opposite is what I found. There is so much awareness of how things could be done better and so much desire on the part of the departments that we serve to improve their business processes and to modernise and digitise what they do.

The biggest challenge for us has been to meet that demand. We have gone about that by first and foremost focusing on recruiting incredible talent—we have a full time recruiter on the team now—and we’ve worked to build up communes that have skill sets and capabilities that didn’t exist in the city before.

Our digital commune is essentially an incredible product studio. They are a mix of designers, developers, content creators, and product managers who can work with the department to help understand the need that they have and craft a custom solution. This is done either in-house or using outside vendors and then to continue to manage and evolve that digital service in a way that allows the department to evolve the quality of their product as technology changes and constituent expectations change.

We are really trying to build up that team that is as agile and capable enough to deliver on ultimately what are some very high expectations that our constituents have of us for what a modern government service practice should look like.

What does the future hold for you?

It’s simply time for my next professional project. I’m going to take a bit of time off to figure out what’s next, but I expect my future work will still sit at the intersection of technology and public good.