Photo: Houston-hosted-the-Cities-Changing-Diabetes-Summit-in-October

Can cities stop the rise of diabetes?

22 January 2018

by Jonathan Andrews

By Jonathan Andrews*

Dr Faith Foreman is facing a daunting task. Houston’s diabetes prevalence rate, presently at 15.6 percent, is set to rise to 21.1 percent by 2045, which will add billions to healthcare costs, with the number of people whose lifestyles are affected rising from 469,000 to 752,000. As Assistant Director for the Houston Health Department, Foreman’s challenge is to reduce this, or bend the curve, to just one in 10 by 2045.

“It’s a very ambitious goal but we, as ‘can doers’, in Houston certainly want to do our best and achieve that,” she says.

Foreman has spent 20 years working in public health and was instrumental in Houston joining the global Cities Changing Diabetes programme three years ago. The city played host in October to the second summit when the global challenge of ‘bending the curve’ to just one in 10 people was announced.

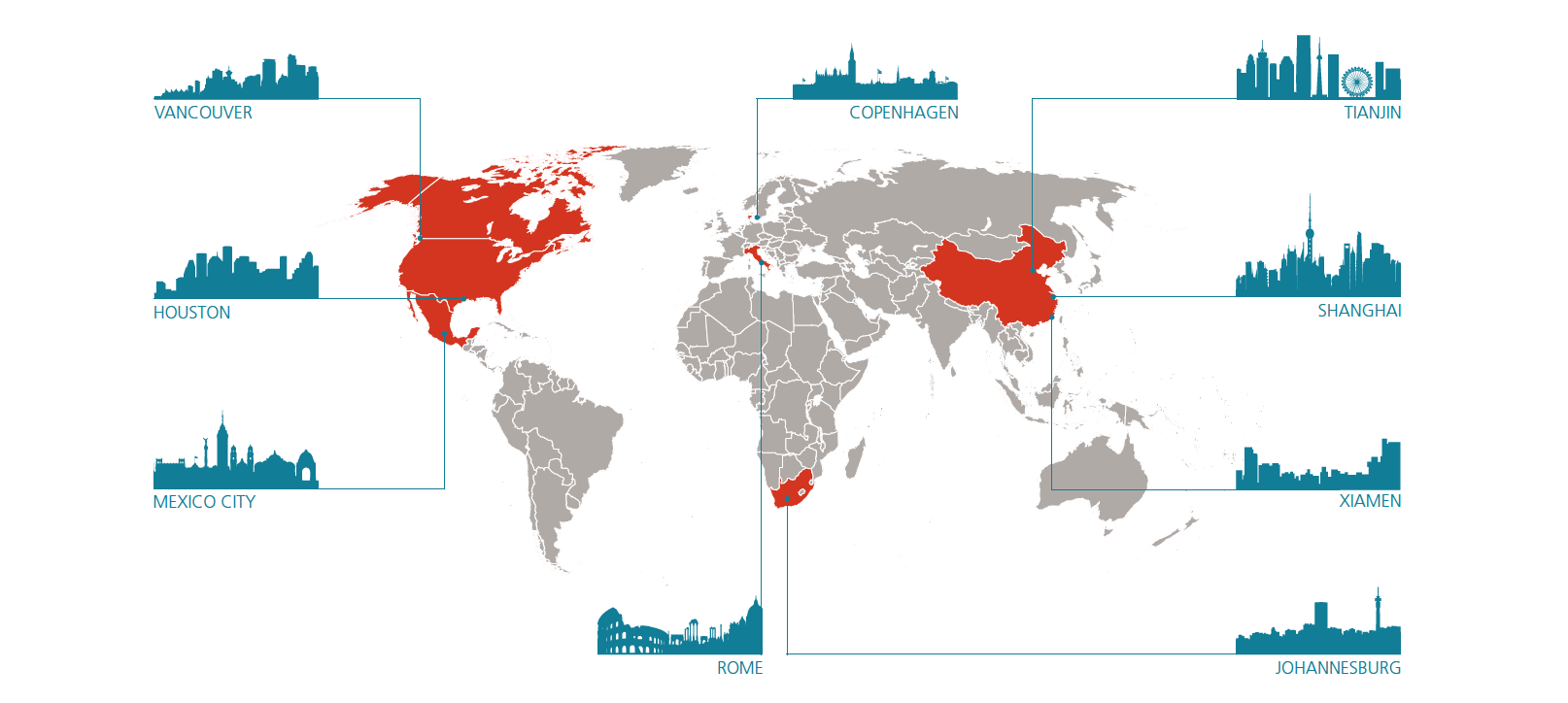

The programme was initiated in 2014 by global pharmaceutical company, Novo Nordisk, and was developed with University College London and Steno Diabetes Centre Copenhagen. Nine diverse cities from each continent from across the world are now part of the programme.

“It took Novo Nordisk three attempts to get through my door,” Foreman recalls. “I won’t take all of the credit but if you wanted to get through to the mayor you had to come through me.”

Foreman reveals that although Houston engages with partnerships all the time around business and oil, this is not often the case with public health.

“I had been in public health so long I was thinking I had done everything but along came the Cities Changing Diabetes programme and I started thinking we could really do something,” she says. “The partnership wasn’t without some apprehension initially, [mainly] because we weren’t used to working with drug companies, but it became natural.”

The global challenge

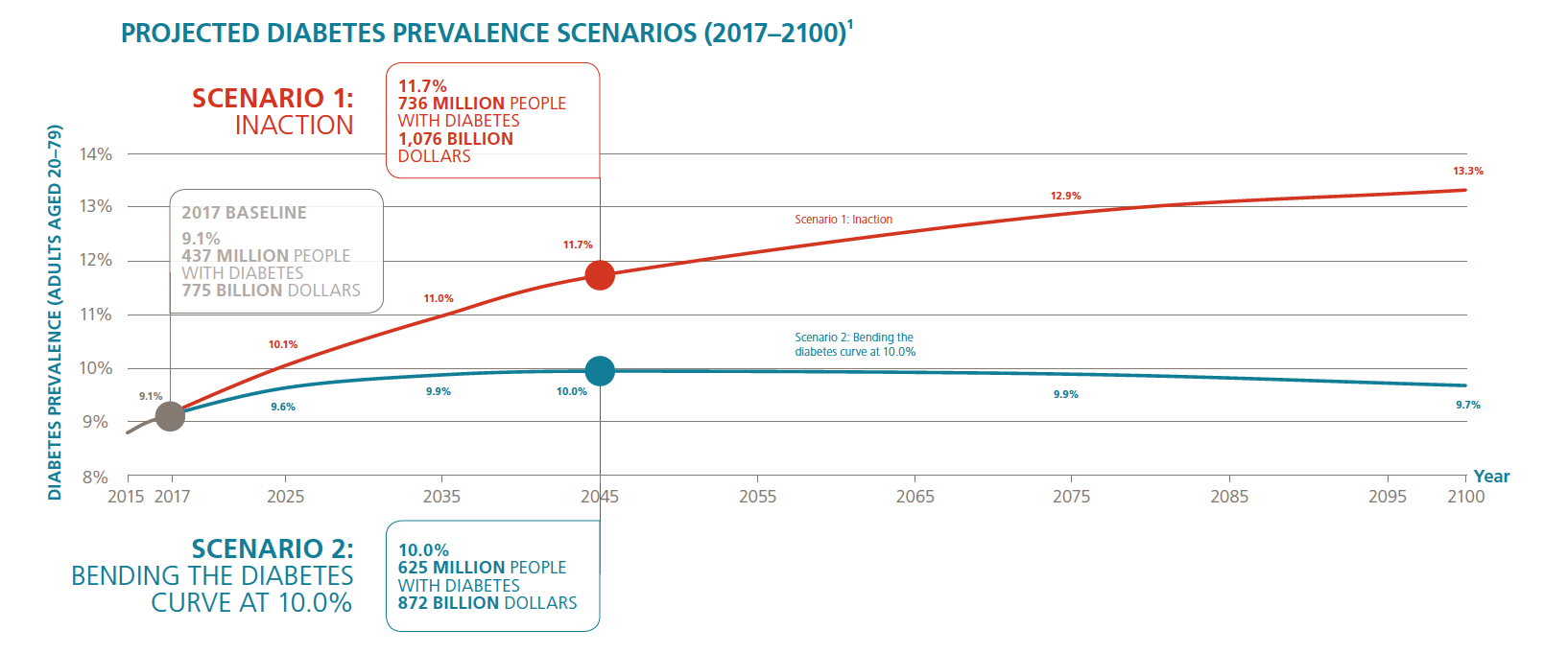

The growth of diabetes is a global challenge facing cities at all stages of development. Around the world approximately 437 million people live with the disease with forecasts showing this to grow by another 300 million by 2045. Two-thirds of those affected live in cities.

“When you add it all up it has significant impacts on societies we live in and puts tremendous pressure on already overstressed healthcare systems,” explains Lars Jørgensen, President and CEO, Novo Nordisk. “We believe that cities are on the frontline of addressing this challenge and where we must take action.”

Novo Nordisk is investing US$20 million over five years (2015 to 2020) in the Cities Changing Diabetes programme. This money is mainly spent on new research specifically aimed at assisting cities, including a new tool box. Non financial resources are provided to enable cities make the most of existing resources and to build the case for further public health investment.

It might seem strange that the largest provider of insulin, the drug necessary to manage diabetes, is actively trying to reduce its market growth, yet Jørgensen–in his position as CEO since January 2017–has renewed the company’s commitment to the programme and believes it is merely the “Novo Nordisk way”.

“If you are engaged in business conduct that doesn’t lead to a sustainable outcome you will have a negative impact on your business,” he says. “Those eventually buying and using your products are not getting the outcome they deserve.”

The company chose to develop the programme and tackle the disease at the city level as he believes “cities have a big impact on health outcomes in the way they are run and designed and can be organised to improve health outcomes”.

Learning from cities

The former mayor of Philadelphia, Michael Nutter, has seen this first hand. During his two terms as mayor from 2008 to 2016, Nutter helped reduce childhood obesity–the leading cause of diabetes–by 5 percent and the rates of adult obesity also declined after decades of increases.

“I worked to promote physical activity by leading efforts to make the city more pedestrian and bicycle friendly, increasing availability of healthy affordable foods and to promote a healthy active lifestyle,” he says.

The city partnered with over 650 corner stores to reduce ‘food deserts’ and to increase and incentivise those stores to sell healthy food. New farmers’ markets opened in low-income communities and the city initiated one of the strongest menu-labelling laws.

“Seven years ago we led the fight that ultimately led to the largest US city passing a tax on sugar in beverages,” he adds. “It was a hard fight and worth fighting for.”

Nutter likens the sugar tax to the indoor and outdoor smoking bans he introduced–which have helped reduce the city’s smoking rates by 15 percent since 2008-and believes that public opinion is changing.

“We will see more and more cities introducing a sugar tax on beverages but you have to make it tangible to something that’s important to people’s lives,” he explains. “We used that extra money to fund Pre-K [Pre-kindergarten classes for children under five]. The moment those against the tax come out against that narrative it appears as though they don’t care about children.”

New partnerships

Copenhagen, although recognised as one of the healthiest cities in the world, is a member of the programme. Although the city’s prevalence rate of diabetes is only 5.1 percent, almost half of adult residents have at least one chronic disease.

A common misnomer surrounding diabetes is that it is the most vulnerable in society that are susceptible–those residents with poor education, low pay or who come from an ethnic minority. Yet, after each member city undertook the programme’s vulnerable assessment analysis, the results were surprising.

In Copenhagen they showed that one of the most vulnerable groups was middle-aged men, who live alone, don’t cook or eat properly, feel isolated and aren’t all that socially active.

In an effort to reach this segment of the population, the city launched a pilot in May 2017, to help build a peer-to-peer social network for vulnerable men to help motivate them to make lasting lifestyle changes.

The programme is housed in the newly opened Centre for Diabetes and will recruit and connect mentors for approximately 100 mentees.

Ninna Thomsen, Mayor of Health and Care, City of Copenhagen, believes that diabetes is one of the biggest challenges the city faces, not just in terms of health but in terms of access to services, and it has become a personal challenge for her to figure out how to reach those most at risk of developing diabetes.

“In Denmark we speak a lot about equality, treating people equally all the time, but if we want to get rid of inequality in health we have to treat people differently,” she says. “The peer-to-peer programme is important and has good results with ethnic minorities but with unemployed men over 45 it is very difficult.”

Thomsen admits that she also needs to think about the cost efficiency and health outcomes of one-to-one peer programmes and says that the city needs to tap into the community better.

“We have a large public sector in Denmark and so maybe we get too lazy with the involvement of the community,” she adds. “We should be much better in engaging the community–churches, football clubs and so on–and not be thinking that the municipal government will come and do everything.”

Faith and diabetes

Houston has long recognised that the way to reach out to a large cross section of society is to go through houses of worship. A 2016 survey revealed that almost half of Houstonians attended a religious service the previous month.

“In Houston when politicians are running for office they come to the church first because they can get more votes and get their message heard by more people,” explains George Anderson, Chief Operating Officer, The Fountain of Praise, one of Houston’s largest churches with over 26,000 members. “So using that same philosophy with diabetes education, church was the best way to get that message out.”

Anderson is assisting the city to launch the Congregational Health Leadership Programme in January 2018. This will involve sending two congregational members from each house of faith on a six-week train-the-trainer course to implement evidence-based primary prevention programmes and a 10-week lifestyle change programme for congregational members already diagnosed with diabetes.

“As well as pulpit messaging, we bring in physicians, nurses and a member of the congregation who has been impacted by the disease,” he says. “It’s powerful because that person, the rest of the congregation knows and respects. It makes it easier for people to identify with.”

While the city has worked with churches in the past on providing education and awareness on breast and pancreatic cancer, what makes this initiative different is that Houston is reaching out to other houses of faith.

“The range of faiths that we are working with is definitely new,” adds Houston’s Foreman. “I certainly know what happens in African American churches [Foreman is a member of The Fountain of Praise] but the diversity and number of houses of faith here, that is new. We aren’t just going to churches but mosques, synagogues and temples.”

Diversity to combat diabetes

During the October summit it was announced that Beijing and Hangzhou would join existing members, Copenhagen, Houston, Johannesburg, Mexico City, Tianjin, Vancouver, Shanghai, Xiamen and Rome.

Although extremely different in population size, climate, density, culture and other factors, Foreman says that there is something to learn from every city and that this has given her new energy to continue the campaign to bend the curve.

“Every intervention may not be applicable to each city but there are elements that we can learn from because although the problems may be similar and the root cause may not be the same, certainly some of the strategies can be.”

Novo Nordisks’s Jørgensen admits that it is early days in the programme and while he cannot yet say if the ‘curve is bending’ he believes that the collection of interventions that work and can be shared through the toolbox will hopefully incentivise other cities to join the movement.

He observes: “In a world where at the national political level things are difficult, and seeing how cities are stepping up–and how more and more companies are focusing on the Sustainable Development Goals–this is quite encouraging and motivating.”

The Urban Diabetes Toolbox

The toolbox is open to all cities to enable city and health leaders around the world to create their own action plan for tackling diabetes. It helps set the goals, map the challenges, understand the areas of greatest risk and vulnerability, and design interventions to halt the rise of diabetes.

It includes;

- How to set a goal.

- Tools to map the challenge (including a risk monitor framework).

- A vulnerability and risk assessment.

- And how to design and deliver interventions.

The toolbox has been developed and built on the experience of the first eight city members. The stories of their research and actions are available to any city and over time will collect the experiences of more cities. For more information see: www.citieschangingdiabetes.com

*This article was first published in Connected Cities, the new app from Cities Today for city CIOs and CTOs on digital urban strategies. To get your free copy, click here