Photo: Charleston-PD-5-551×369

How technology is helping cities to combat crime

04 October 2012

by Richard Forster

In an economic downturn, there are generally two certainties for cities: crime will increase and city budgets will be reduced. Jonathan Andrews reveals how predictive software is helping mayors and city police departments to tackle crime on a reduced budget

The old police method of sticking coloured pins onto maps to record crimes is having a 21st century makeover. Commonly used to record where crimes did occur, and to draw some basic predictions, the new technology is enabling police forces to predict, with far more sophistication, where future crimes will occur.

Predictive analytics software has been used in academic circles since the 1980s, as well as in the banking industry to assist with statistical calculations, but in the last few years, it has begun to be used for policing.

In 2006, US technology company IBM was one of the first companies to employ the software for law enforcement in Memphis, USA, and it is now working with 10 cities in the US and UK. In Memphis, the software has been accredited with reducing the city’s serious crime by more than 30 percent, from 2006 to 2010, including a 15 percent reduction in violent crimes.

“It’s not like the film Minority Report or science fiction stuff,” says Mark Cleverley, Director of Public Safety Solutions at IBM. “It really is more aggregate, using data in volume, looking at trends, finding hotspots and then being able to deploy resources more efficiently and proactively, either to deter criminal activity or to arrest criminals.”

Although various models exist, most predictive analytics comprise of collecting information from existing data to determine criminal patterns. The software predicts where certain crimes could be committed enabling police forces to send officers to those areas.

IBM was able to rely on the support of researchers at the University of Memphis, who were very interested in how academia could help police operationally. Cleverley admits that the combination of the police department and the university working together accelerated the impressive results and IBM is currently exploring further avenues of collaboration between academia and policing.

“In Memphis we found a police leader who wanted to get more effective in policing and was very conscience of trying to do more with less,” says Cleverley. “In the US more than 70 percent of police departments have less than 20 people so you don’t have a lot of scope for specialty in analytics or technology. Academic involvement potentially provides extra resources to a police department.”

Small city success

Across the country in California, one of the smaller police departments, which Cleverley referred to, has been trialling a different version of the software with equally impressive results. The city of Santa Cruz, with 92 officers, was hit by a 30 percent rise in calls for its services while at the same time suffering a 20 percent decline in staff—an all too familiar story for many cities in a financial crisis.

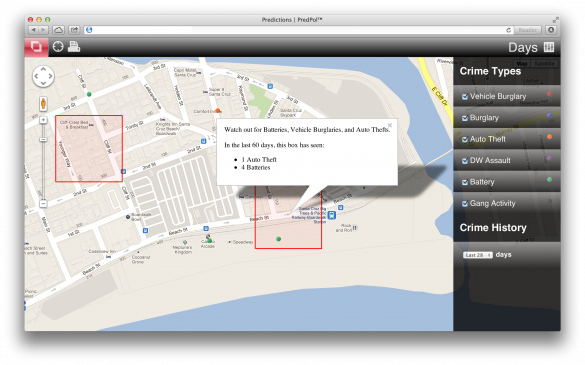

Zach Friend, the public information officer and crime analyst at the city’s police department, came across research being conducted by the University of California, Los Angeles and a precinct in the Los Angeles’ police department. Initially based on a mathematical algorithm for predicting earthquake aftershocks, Friend spent time building the city’s own operational model working with the police, software company PredPol, and academics from the university. Since the launch in July 2011, the city has seen a 19 percent reduction in commercial, residential, and vehicle burglaries.

Publishing crime statistics is a politically sensitive business with tweaks and massaging of the figures common place but Friend emphasises that the use of the software was the only variable.

“Normally what you see in trends is either violent crime goes up or down as a group but we didn’t see the same reduction in other property crime types,” he says. “We didn’t have more cops, we didn’t change shifts, or times, nothing changed but that.”

The then mayor of Santa Cruz, Ryan Coonerty, was equally happy that his police department was taking the initiative in introducing the software but still held some doubts.

“I really only became convinced after seeing the drop in crime,” he says. “It was the biggest drop in my seven-and-a-half years on the council. You would hear of officers going to a certain area at two o’clock in the morning, not believing that that was where the crime would necessarily be, but curiously finding someone about to break into an apartment.”

The Santa Cruz software, called PredPol (predictive policing), delivers reports to smart phones, tablets, PCs or even on paper, identifying 150 square metre locations which can be specific to a crime type and to shifts. Officers are briefed at roll call on the highest probability hotspots for that day and asked to give extra attention to those areas.

Rank and file acceptance

Although the technology is relatively basic and easy to implement, some growing pains still existed. “Law enforcement is traditionally conservative when it comes to change,” says Friend. “We have to ensure that there is a ‘buy-in’ at the officer level.” According to Friend, time is needed to explain the software, why it is needed, and crucially the need to get input from the police officers.

IBM’s Cleverley agrees but says that the technology is a force multiplier, which takes the insight and knowledge of a regular patrol officer, expands upon that, and then codifies it into a model of what is happening in a community.

In the beginning, the younger officers in Santa Cruz were faster in their uptake of the technology. “Younger officers use more technology at home than they use on the job because we don’t provide them with the amount of technology they are used to using,” admits Friend. “But as time has gone on, it has become more equal.”

Legal concerns

Although predictive analytics is widely receiving plaudits for its assistance with intelligent policing, legal concerns have been raised with regard to the possible abuse of such technology.

Andrew Ferguson, Assistant Professor of Law at the University of the District of Colombia, USA, has written several papers on predictive policing and believes that the technology could be open for abuse and misinterpretation.

“The collection of the data and the inputting of the data are rife for either mistake, error or manipulation,” says Ferguson. “It’s going to be very difficult for courts to analyse it as a whole new world of expert testimony will be needed to see whether or not the data is correct. Algorithms will have to be revealed, and they’re going to have to have people understand what algorithms can actually do and mean to be able to evaluate them in court.”

Cleverley believes that while the technology could be used to threaten civil liberties it can equally protect them. “A system like this automatically gives you very robust auditing capabilities, like who has looked at the information, when they did, what did they do with it, these sorts of things are far more transparent than when paper-based systems were the norm.”

The biggest grey area raised by the legal profession is whether or not a police officer has reasonable suspicion to stop and search a person in a particular location. In the US, and in many other common law countries, police need to have good reason and specific, and rational, facts to stop a suspect.

“An officer is going to say, ‘Look, I went to a particular place because the computer told me to go that place’,” Ferguson says. “Without some way of cross examining a computer or evaluating why this algorithm told them to go there–or whether it’s accurate–is going to be a weighty factor.”

Friend from Santa Cruz, says that the key about the system is that people are not the inputs—it depends only on data for time, date, crime type and location. “It just produces squares,” he says. “It doesn’t say ‘Here are the three people to go after’. It doesn’t direct massive amounts of resources into low-income or minority areas. It’s running probabilities across the entire city, so therefore resources are employed everywhere.”

Currently the software is running trials on crimes rather than simply burglary and theft–drug crimes being one–but the technology does have its limits.

“One is a lack of data,” Friend says. “You have to have enough data for it to work and so some very small cities may not have enough violent crime for the model to apply.”

Friend also says it does not work well on homicides or domestic violence. “Crimes of passion won’t work,” adds Friend. “It works well on assaults, robberies and fights, and those are the crimes we are now expanding into.”

Cleverley says that IBM is exploring options through sharing the software, whereby multiple police departments, on a hosted basis, can use this technology.

“The capabilities that a Memphis has, not every city could muster the resources to do it at a 20 person police force level but maybe if you took 10 or 20 of those police forces and helped them to do it through cloud technology then that might be a good model to take this forward.”

Implementation costs

In terms of costs, Friends says that PredPol charge an amount based on population size. “It doesn’t cost us anything as we built it but a city near us with 150,000 people pays, I believe, US$25,000 a year.”

Friend says their software is based on what police departments can realistically afford, and likewise it has to be less expensive than hiring more police officers or analysts. “If you could hire 50 percent more cops, you probably wouldn’t need a system that allocates limited resources more efficiently but nobody is facing that.”

Implementation is simple. As it is a cloud-based program, no additional staff are needed nor is there a requirement for further training. Friend says it was built into their system in one afternoon, and as everything is automatically generated, the algorithm updates at the same time an officer writes a report and puts it into the database. “You can log on and get an updated prediction map almost instantaneously,” explains Friend.

With IBM’s system, Memphis has calculated the cost of the software at an average of just under US$400,000 a year. Although considerably more expensive IBM are quick to point out that they are able to bring enormous support that such a global company has, and tailor the software to each city’s needs.

“We bring all of IBM’s experience to the table,” says Cleverley. “We deliver a very complete solution that has proven to be a great asset to law enforcement, and provide clients with what they need today to address their current needs.”

Future of predictive analytics

While historically crime fighting was devoted to improving response capabilities— arriving faster, following up investigative leads quicker, and then making arrests sooner— this is now moving to more proactive options. “I think we are at the beginning of the journey and not even halfway through it,” says Cleverley. “Now, we can add the ability to do things more proactively. Before an event happens we can deploy resources that might deter crime from happening or might allow us to respond to it better.”

Experts also believe that predictive analytics will not just be restricted to crime fighting but will be expanded to many areas as the public safety landscape becomes more holistic, involving, fire, ambulance, police, education, health and social welfare organisations.

For the moment predictive analytics is capturing the attention of city leaders from many other US cities, and from Israel, Brazil and India.

As the former mayor of Santa Cruz says, the technology is attractive as it gives city leaders the ability to take action now with almost instant results. “As mayors, whether liberal or conservative, we all campaign on reducing crime, and usually there is very little we can actually do about it once we are in office,” says Ryan Coonerty. “A program like this gives us the opportunity to actually provide something to our community that we promised to deliver.”