Photo: Oakland-riots_Thomas-Hawk-WEB

Can US cities heal the rift between police and citizens?

21 September 2015

by Nick Michell

Few could have predicted the extent to which issues related to policing, crime and race relations have come to divide urban America in ways that have left public officials worried about how to maintain the fractured peace and engender a more stable future for their cities. Tom Teodorczuk spoke to mayors and White House officials to find out what national and local governments are doing to tackle urban insecurity

Not since the late Rodney King pleaded, ‘Why can’t we all get along?’ during the Los Angeles Riots in 1992 has public safety in the US been in so precarious a position. Flashpoint incidents include the shooting in August 2014 of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri and the subsequent furious reaction to the decision of a St. Louis County grand jury not to indict the police officer responsible for Brown’s death. Last December the decision of a Staten Island, New York, grand jury not to indict a white police officer for choking to death Eric Garner, a black man accused of selling cigarettes on the street, provoked similar outrage.

Relations between the police and minority communities in US cities have been tested to the limit and further challenged by tragedies such as the assassination of New York City police officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian

Liu. The unrest continued into 2015 with a series of riots in April engulfing Baltimore in response to the death in police custody of Freddie Gray.

Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, the Mayor of Baltimore, told the United State Conference of Mayors Annual Meeting in San Francisco last month: “Nearly two months ago, my city experienced one of its darkest periods in nearly 50 years. I can’t tell you the heartbreak seeing my city descend into that type of violence and unrest. I told my state legislature earlier this year: Don’t think it can’t happen in any of your cities. At the time, I was referring to Ferguson. But I am now unfortunately referring to my own city.”

These dark periods have cast a shadow over US cities and raised the question of what mayors can do to maintain safety and security. Cities Today asked this question to Steve Benjamin, Mayor of Columbia, South Carolina, a few days after a racially- motivated gun massacre at the Emanuel AME church in Charleston, an hour’s drive away from Columbia, the city where the suspect hails from.

“As a mayor, I’ve always made public safety and investing in law enforcement a priority. Our budget this year increased by US$3.2 million, US$2.8 million of that went to our fire, police and emergency services,” said Benjamin, who had personal connections to several of those who died in Charleston. “In my city we have 130,000 people, we have 400 sworn officers and we invest in community policing, education and mental health. All these things go to making a stronger, healthier and better society but my greatest concern is that we cherry-pick individual smaller issues and we don’t have a chance to have longer, tougher conversations that go towards creating a healthier body politic.”

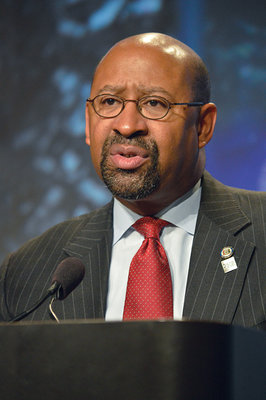

For another of America’s leading mayors, Michael Nutter, Mayor of Philadelphia, crime prevention depends on effective communication between elected officials and their constituents. “Part of the key is letting the citizens know we have a plan for public safety,” says Nutter. “It’s about having officers on foot patrol, community policing and about officers having respect for citizens and citizens having respect for officers. That respect has resulted in citizens giving us information that we need in order to provide high quality public safety. We’re constantly training and re- training our officers in how to engage with citizens. Sometimes we make mistakes but we lowered the crime rate which the citizens appreciated.”

But as Nutter emphasises, while you can put in place as many preventative measures as possible, it is impossible to know what any one person is ever going to do at any point in time. It was unimaginable that someone would shoot 20 children and their teachers in a school and equally unimaginable that someone would kill nine people in a church.

“What safer two places could there be than an elementary school or a church?” says Nutter. “I respect the second amendment of the United States but I have a personal right not to be shot.”

John Giles, Mayor of Mesa, Arizona, says mayors who painstakingly prioritise investing time and resources on the issue usually preside over safer and more secure cities. “Mesa is a large city with a population of half a million people and a lot of racial diversity and a majority minority school district,” he notes. “But we’re a relatively safe city compared with other cities of our size. We try to do a lot of outreach and involve the faith community and the ethnic community as much as we can and pay close attention to the statistics of what’s going on in public safety to anticipate problems before they occur and not let situations fester.”

But as Giles says, the truth is there could be an incident in Mesa tomorrow that would be on the front page. “You can’t take it for granted anywhere in the United States,” admits the mayor.

Ashton Hayward, Mayor of Pensacola, Florida, stresses the need for mayors to be innovative. He recalls hearing about the concept of body-worn cameras worn by police when they were being piloted and worked with his police chief to bring them into his municipality.

“We’re one of the first cities to introduce body cameras,” he says. “We had to train our police officers but most were open to it and embraced transparency.”

Hayward says that security has become the number one issue for a mayor in any city whether it’s Manhattan, Chicago or Pensacola.

“Every night I go to bed thinking about public safety and what’s happening in our city,” comments Hayward. “The biggest problem politicians face today at a national and local level is the fact people don’t trust their leadership, so they hide. Everybody in Pensacola knows who I am. I like to think I’m trusted.”

Many Republicans and Democrat mayors might differ on their attitude to gun control but there is a nationwide consensus on safety and security being the problem of our time.

“I think it’s a bipartisan issue,” says Mick Cornett, Republican Mayor of Oklahoma City. “It’s [gun ownership] part of our country’s history. But when these events occur, the questions we ask are how did this person get their gun and could this have been averted? In every case there are things that could have been done. Typically it’s somebody that could have stood up and tried to stop it. Mental illness plays a key role in many of the types of events we’re talking about. We have been underfunding mental illness.”

Beyond offering leadership and preaching unity in times of crisis, the US government is seeking to expand its role in ensuring America becomes more safe and secure. In the past 12 months, the White House has hosted summits for improving law enforcement and community relations and combating violent extremism. Congress has allocated US$7 billion of seed money to boost the government’s digital security, including building up the broadband network for law enforcement, and it has encouraged the deployment of Citistat, a data-tracking and management tool that monitors crime and security statistics in cities.

“People are increasingly now using technologies for initiatives like Citistat that allocate law enforcement resources where they will have the biggest impact,” Tom Kalil, the White House Deputy Policy Director for Science and Technology, told Cities Today. “We’ve also launched the Police Data Initiative which is about trying to restore some of the trust that has been eroded by recent events between law enforcement and the community related to transparency.”

Technology is fuelling innovation but it is also causing cities significant headaches. “Social media is a double edge sword,” observes Doug Smith, Senior Advisor at Chesapeake Crescent Initiative (CCI), a public- private collaborative that supports technological innovation in security and energy in Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. “In Baltimore it was used by individuals looking to create the unrest but by the same token it gives people the ability to truly and peacefully demonstrate when something’s not right and it also gives the appropriate authorities the capability to know there’s likely to be an event in a square because this is what social media is talking about. For example Verin [a leading provider of security intelligence solutions] which partners with CCI, has the ability to extract data and intelligence, parse it and route it to the appropriate bodies as a law enforcement tool.”

Tomorrow’s technology could transform one of today’s most sensitive security areas–shootings in schools. ShotPoint, an acoustic shooter alerting system, uses a private fibre optic network, which enables police to respond quickly in the event of an outbreak of gun violence. School shootings continue to blight America’s landscape, the most recent example being the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, when 20-year-old Adam Lanza killed 20 children and six staff members.

Virgina tech company, Databuoy, has partnered with the city of Ammon, Boneville County, Idaho, to trial ShotPoint in schools. The experiment proved so successful that the integrated security system is set to become a permanent fixture in Ammon schools by the end of this year. Bruce Patterson, Technology Director in Ammon, admits he had to win over various vested local interests to implement it in schools. “It was a good application of technology but we had to work to bring the school district on board because they already had their camera system and they were not necessarily wanting to open it up,” says Patterson. “The sheriff ’s department was uncertain it would work all the time and were asking questions about liability and responsibility. But once they saw it, they got on board and now their question is: ‘Can we keep the system?’”

For now a bridge clearly needs to be built connecting local communities’ escalating security fears to the private sector tech boom that has been pioneering safety innovations. The White House intends to construct that bridge.

“We held the White House summit to counter violent extremism in order to introduce the private sector to the problem and try to encourage public- private partnerships,” says Brette Steele, Senior Counsel to the Deputy Attorney General at the US Department of Justice. “We are absolutely looking for more public-private partnerships both in investment and technology.”

Steele oversaw a cross-collaborative initiative whereby the White House, Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI piloted with the City Governments of Boston, Los Angeles, Minneapolis and St Paul, Minnesota, to formulate approaches to eradicating extremism by identifying its root causes through building partnerships with law enforcement officers, city officials and education personnel that go beyond community policing.

“One of the baseline principles in countering violent extremism is that everyone has a role to play,” Steele notes. “Not just law enforcement but community leaders and industry leaders as well. The question is: ‘What role can everyone play?’”

That’s also the key question beleaguered city mayors are focused on answering to restore faith among their anxious, and in some cases shattered, communities.

“You take some basic steps but once in a while you’ve got to take a leap,” says Mayor Benjamin of Columbia, South Carolina. “Recent events provide an opportunity for us to do some real introspection on the major issues that have been facing us and find consensus but we’ve got to be thinking long-term about whether or not we’re doing everything we can to make the American dream real for all people. That’s a much deeper, systemic challenge that I believe mayors are uniquely prepared to address.”