Photo: Jack Hunter on Unsplash

How Prague is shaping its circular economy

29 July 2021

By: Laxmi Adrianna Haigh, Circle Economy

Lying at the heart of Europe is a city otherwise known as the City of a Hundred Spires, renowned for its abundance of gothic architecture and UNESCO world heritage stamp. But one thing you may not know about the Czech capital of Prague is that it has fast become a trailblazer in establishing a local circular economy.

Cities are the consumption centres of the world: hotspots of resource use and global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. They’re also rapidly growing – Prague’s population alone has jumped by 11 percent in the past 40 years. The circular economy, with its suite of strategies suitable for urban policymakers, can deliver substantial climate mitigation opportunities, social benefits and economic advantages.

Today, Prague boasts a population of nearly 1.5 million and an economy that has swapped industrialism for a high-tech, trade and services-oriented character. To tap into the momentum its new service-economy offers, while addressing urban challenges, supporting nature and securing social benefits, the city has placed the circular economy at the heart of its city planning and climate mitigation ambitions.

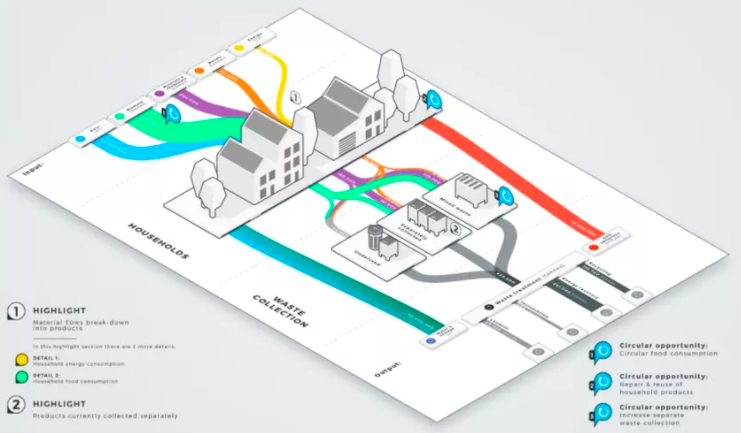

To support this goal, in 2019 the Amsterdam-based impact organisation Circle Economy, in collaboration with the local NGO INCIEN and the City of Prague, analysed the material flows, GHG emissions and value generation of Prague’s economy. Their goal? To provide the city with action plans for key industries to embed the circular economy into their practices.

Two years have passed since the ‘Circle Scan’ and the circular transition in Prague is well underway.

“The Circle Scan helped us set priorities and measure the scale and issues of what we were dealing with. This allowed us to focus on what matters. So, we’re not just focusing on plastic straws, but on larger flows like closing the biomass loop, or looking at our tonnes of construction and demolition waste. There are so many bigger problems – and opportunities,” said Petr Hlubuček, deputy mayor of Prague for the environment.

A second life for bulky waste

Each year, Prague households consume approximately 307,000 tonnes of non-food products. Of this, nearly ten percent is bulky waste – materials or items too large for household waste, such as electrical goods, appliances and furniture – destined for landfill. And as the average household income has risen, so has the level of tossed bulky waste. The Circle Scan identified the potential to reuse 70 percent of this, giving furniture and appliances a second life and reducing the overall demand for brand new products.

Bringing to life the action plan laid out in the Circle Scan, Prague now touts a growing network of Re-Use Points throughout the city: cashing in on the value this ‘waste’ provides when the circular strategies of reuse, refurbish and repair are utilised. In only half a year of the pilot being active, nearly 2,000 pre-loved items were processed: the equivalent of 14 tonnes.

These reuse points have been integrated into collection yards – so far, three out of the 19 in the city – and upgraded to feel vibrant and accessible for all citizens. Praguers can drop off their unwanted yet still-functional furniture, sports equipment or appliances, amongst other items, which are then uploaded to an online portal and can be collected for free by residents, NGOs and charities.

The city also plans to recreate a Reuse shopping centre – a reuse wonderland where everything sold is second-hand or repaired. Watch this space, notes Hlubuček.

Turning food waste into biogas

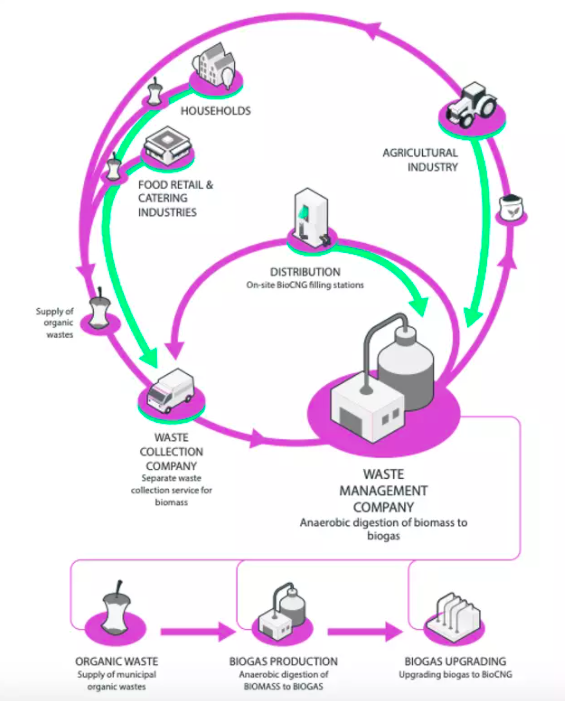

The Circle Scan pinpointed a major waste stream in the Czech capital with huge untapped potential: food waste. In Prague, households consume more than 950,000 tonnes of food each year – with roughly 100,000 tonnes of domestic food and kitchen waste entering low-value recycling streams such as being burned for energy. In an ideal circular city, material flows would be collected separately to retain their value at the highest level for as long as possible – food waste can be returned to the soil as organic fertiliser or converted to biogas, for example.

To use its tonnes of food waste as a resource, Prague set the ambitious goal of separating 70 percent of municipal waste at the source by 2035; current separation rates stand at 31 percent. To start, it became the first Czech city to implement household food waste collection. This is currently in the pilot phase in three districts and hopes to be city-wide by 2026.

The collected food waste is converted into biogas and used to power waste management trucks. With the instalment of a large bioCNG plant planned, the city hopes to see the entire fleet of waste management trucks powered by household food waste in the future, utilising waste as a resource and cutting GHG emissions (the trucks release 58 percent fewer pollutants into the atmosphere than diesel-fuelled trucks).

Also, excess energy will be pumped back into the grid and excess waste transformed into fertiliser for local agricultural projects. The city also targets minimising consumer food waste habits: waste prevention is touted by city billboards, urging residents to “buy only what you eat”, and environmental campaigns are integrated into schools.

Organic farming

Given that 80 percent of all food is expected to be consumed in cities by 2050, operating in a circular manner where food production regenerates rather than denigrates and where food waste is designed out can bring massive environmental benefits. Current farming practices across Europe can be GHG emissions-intensive, contribute to a loss of grassland biodiversity and use dangerous pesticides, which can also result in pollution leaking out into water supplies. In Prague, the City Scan identified that agricultural and material extraction alone were responsible for 234,360 tonnes of GHG emissions a year.

We’ve already seen how Prague is tackling household food waste, but it’s also innovating with a circular procurement strategy to regenerate ecosystems and provide healthy food for the locality on city-owned land.

The city owns 1,650 hectares of agricultural land – currently, 500 hectares of this is leased to farmers – yet it comes with a sustainable catch. Farmers must follow organic and circular agricultural principles, namely: no pesticides, no fungicides, use of organic fertilisers and respecting crop rotation. Engaging with farmers and giving priority to organic and circular practices is a strong avenue for cities to take in moving to a circular food system. Co-benefits of the practice can include diversifying a city’s food supply, fostering biodiversity, reducing packaging needs and shortening supply chains.

Circular strategy

In only three years, Prague has become a regional leader in circular innovation. This successful journey has been a result of various factors. Besides the Circle Scan, top political endorsement and stakeholder management has been instrumental: with a dedicated committee and steering group for circular economy, the circular economy has been embedded into the daily decision-making processes of the city.

For many cities with sustainable and circular ambitions, knowing where to start can be the biggest barrier. While there may be experts on circular activities taking place, a holistic overview of a city’s overall resource consumption and waste patterns is often lacking. This type of high-level view of the interconnected systems can support the city in locating priority challenges and opportunities. Involving diverse stakeholders is also key, and understanding how they can contribute to a more circular city.

“The magic of the Circle Scan is giving the space and energy needed to get relevant stakeholders aligned around the topic of the circular economy, and to identify the business case for the city and turn it into reality,” says Vojtech Voseky, chairman of the circular economy steering group in the city.

“This has happened in Prague and kickstarted all these pilots,” he adds.

Image: Jack Hunter on Unsplash