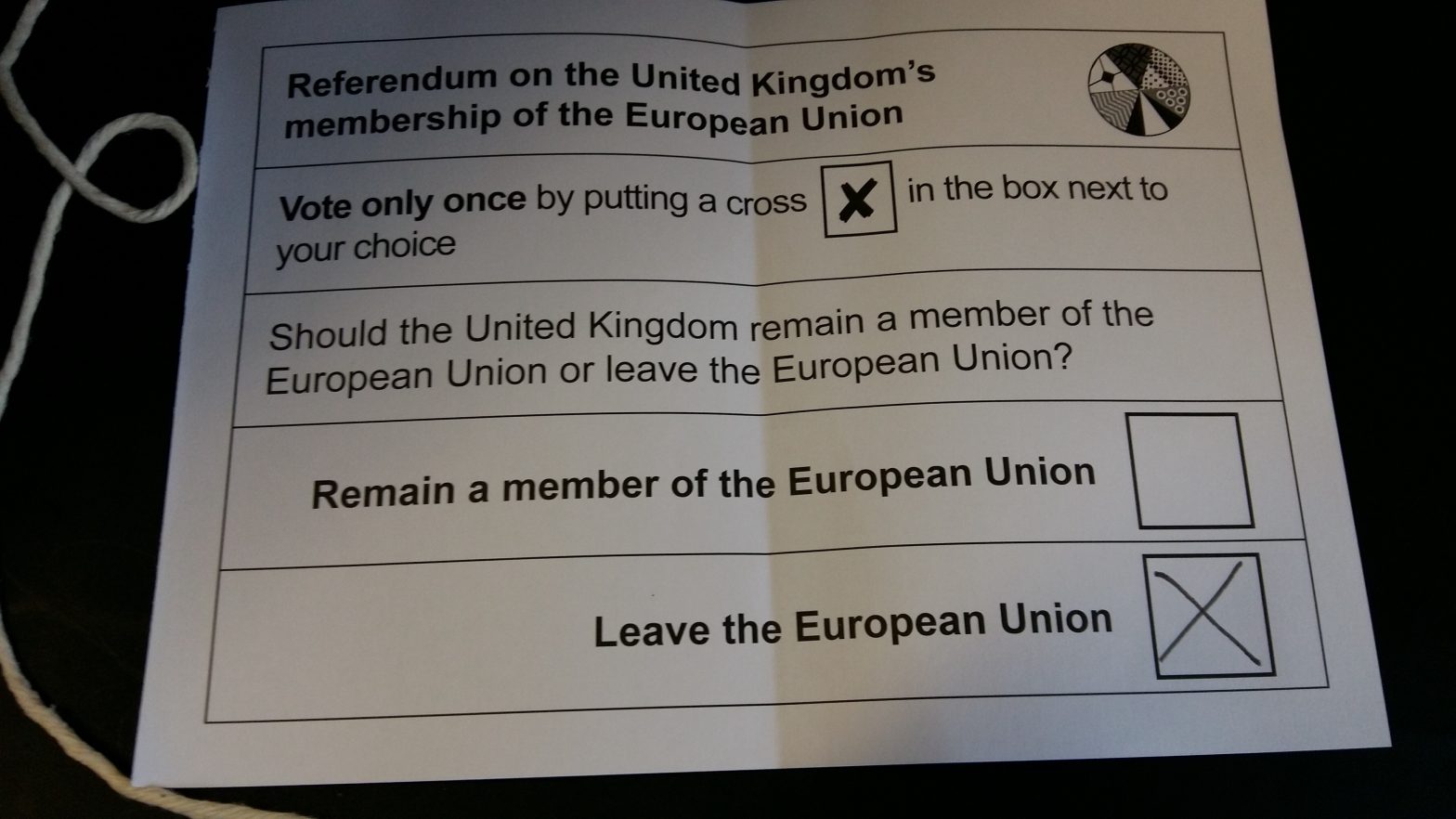

Photo: flickr

Will Brexit stall the UK’s smart city programme?

17 September 2016

by Jonathan Andrews

Cities Today research has revealed that UK organisations have coordinated Horizon 2020-funded projects (an EU research and innovation programme) worth €1.9 billion. Since 2014, the UK has been the most prolific user of Horizon funding, working on a total of 3,070 projects, far more than second-placed Germany, which was involved in 2,762 projects with UK institutions, companies or local authorities having benefited from nearly €1 billion of the funds.

Those projects include some of the UK’s leading smart city lighthouse projects such as London’s Sharing Cities and Communities Programme, Bristol’s Replicate project, Manchester’s Triangulum project and Birmingham’s Opticities partnership.

The Horizon sums alone might be worrying though not insurmountable for the UK government to replace. However, there are other bigger amounts of European funding available to the UK public sector, which are now under threat from Brexit.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) provided £5.6 billion for 40 projects across the UK during 2016. This sum supported nearly £16 billion of overall investment including four new hospitals, five university campuses and 77 new schools. Furthermore, the bank is the largest lender to the UK water sector and has invested £1 billion in social housing in London and Scotland alone.

“There are a whole range of areas where only now the sudden challenge of a key loss of financing is becoming clear. Utilities certainly realise it and cities and devolved administrations are also starting to consider the loss of investment,” says an EIB spokesperson.

For now though, despite governments in the UK and across Europe positioning themselves for the complex Brexit negotiations to come, everyone is keen to push the message that it is business as usual.

Shortly after the referendum the European Commission issued a statement assuring UK organisations that until the UK leaves the EU, EU law continues to apply to and within the UK and “this includes the eligibility of UK legal entities to participate and receive funding in Horizon 2020 actions”.

“In terms of our activities on live projects such as our Smart Cities and Communities Programme, yes, it’s business as usual,” says Andrew Collinge, who is the Greater London Authority assistant director with responsibility for smart city projects. “We are being good public servants and getting on with it and delivering 100 percent against the plan that was set out at the start of the programme.”

The European Commission contributed €25 million to the programme of which London received around €7 to 8 million. It is London’s biggest Horizon project in terms of the scale of European funding.

“We have three years of delivery and two years of evaluation on that programme so by the time that article 50 is invoked and then negotiations are carried through, I think that the reality is that we will be on the other side of delivery and on to evaluation anyway,” adds Collinge.

Talking at a recent presentation on the €13 million Opticities programme, Birmingham’s project leader Steve George lamented: “Unfortunately we’ve got Brexit, which means potentially this project goes no further.”

Opticities was led by the French city of Lyon in partnership with Birmingham, Gothenburg, Madrid, Turin and Wroclaw. The plan was to take the results and use them to assist 50 cities around Europe. George says the Commission is keen to see the project replicated around Europe but it might need to do it without Birmingham though he adds defiantly: “For Birmingham, regardless of Brexit, we will take forward the tools we have developed here. There is no reason why we can’t go it alone.”

London is the lead city on the Urban Platforms project part of the European Innovation Partnership. That work also continues.

“While we negotiate Brexit then I absolutely do want things to continue as usual,” says Collinge. “We have a lot to o er our European colleagues–in this case on data and urban platforms.”

The Mayor of London’s office has made it very clear that it expects the government to make good on the promises the Leave campaign made pre-referendum to replace European funding. In August, the UK Treasury gave its first indication that it might do this with a very limited commitment to guarantee domestic funding for EU-backed projects.

However, reading carefully, it became clear the Chancellor was merely offering reassurance that projects, which the EU agreed to fund before Autumn 2016, would continue to be funded (by the UK government if necessary) even if the project continued after the UK has left the EU. There were absolutely no promises about how the type of projects that were funded by the EU will be funded after the UK has left the EU.

Despite the “ifs” and “buts”, some city leaders involved in European Commission-funded projects took heart from this statement.

“This comes from the highest levels of government and gives us some long overdue clarity,” says Mark Duncan, Manchester City Council’s team leader on the Triangulum project. “If at any point the EC stopped funding UK partners on approved projects, the UK government is agreeing to make good any shortfalls.”

The big money

But while the UK government may agree to make good shortfalls from research funding like Horizon 2020, which has been essential for universities, research institutions and cities embarking on smart city research and development, replacing the £42 billion that the EIB has pumped into the UK during the past decade may prove rather more challenging.

The picture is further complicated by the fact that the UK has a 16 percent shareholding in the EIB, the Chancellor of the Exchequer is a governor and the UK has a seat on the board.

A spokesperson points out: “The EIB Statute does not contain provisions for shareholders leaving the EIB but given the Brexit vote it can be expected that the role of the EIB would be discussed in withdrawal negotiations and the EIB’s future lending in the UK considered by the bank’s 28 EU member state shareholders.”

Unlike other European countries such as Germany, Italy or the Netherlands, there is no national infrastructure bank in the UK that could replace the EIB overnight.

“There is £1 billion of new social housing in London and Scotland that might not have happened without the EIB’s involvement,” says the EIP’s spokesperson. “If we threw modesty aside, that’s something we would say but there are 30 universities with new campuses and they have said they wouldn’t be able to do it without the EIB’s help. If it ends, that’s clearly under serious threat.”

The EIB does fund projects beyond the EU but these funds tend to be reserved for projects in developing nations. Similarly, the European Free Trade Association countries benefit from their association with the EIB–but Norway, Iceland and Switzerland have received just €1 billion from the EIB compared to €43 billion invested in the UK in the past eight years.

Similarly, non-EU organisations can take part in Horizon projects through the international participation scheme but funding opportunities are more limited and these tend to be reserved for developing nations.

Existing UK sources

So what are the sources of UK funding? Innovate UK funded the Future Cities Programme with 30 councils each receiving £50,000 to develop feasibility studies before Glasgow won £24 million to implement its proposal. Bristol, London and Peterborough were each awarded £3 million to implement part of their plan. However, this is the first time that Innovate UK has directly funded a city–it is normally used to nance small and medium-sized businesses.

Mike Pitts, Head of Urban Living and Built Environments, Innovate UK, points out: “A lot of work we have funded here has gone on to form the basis of [Horizon] projects so the two things have worked together quite well.”

Indeed, the work on the 30 feasibility studies for the Future Cities Programme has continued and has resulted in the cities raising a combined £107 million from a variety of sources including some from Europe and some from the private sector. Belfast, Bristol, London and Peterborough all used the work as a basis for future smart city projects.

Milton Keynes secured over £66 million of the £107 million itself–a large chunk of it for its low-carbon urban transport zone, which gained a big government grant for its pioneering work with autonomous vehicles. It also won £8 million from the Higher Education Funding Council for England and £8 million from 20 partners, including telecommunications company, BT, and the Transport Systems Catapult (part of Innovate UK).

Despite Milton Keynes’ success, public sector sources say that the money they can get from the private sector or other sources such as Innovate UK is not of the same magnitude as they can get from the European Commission.

“The Lighthouse projects are of a different scale and UK cities have been very successful with winning that level of funding but we should separate [Horizon] funding from the European Regional Development Fund structural and investment funds,” says Innovate UK’s Pitts, who points out that his organisation’s remit is to help UK businesses grow faster not to fund the public sector.

“There is no denying that the European Commission has been a rich and really valuable source of funding for smart city demonstrator activities,” says Collinge. “The important thing to remember is that although we are talking about relatively large chunks of money, it still only amounts to demonstrator activity. Hence, our own bid has a focus on business models and funding and trans-national European financial innovation.”

Part of Collinge’s Sharing Cities programme includes a plan to establish a €500 million smart cities fund for cities across Europe.

“I think part of the reason we were successful in our bid for that funding round was London’s financial prowess and competence,” says Collinge. “That starts to look a little bit different if the fund we are trying to create has a lifetime that stretches beyond Brexit. While London is still hugely financially powerful, we have to be aware that the fund itself might have to operate from elsewhere–within the economic area that emerges post-Brexit.”

Collinge’s team is building business models around use cases, such as smart lampposts, sustainable energy systems and urban platforms. He also hopes to win seed funding or technical assistance funding from the EIB for each of the individual use cases. Then discussions with investors from other sources can begin to build the investment fund.

“One of the things we are really keen to do is to make sure we share the opportunity with the other five city programmes and pick the good things they are doing and turn them into investable propositions,” says Collinge.

There remain doubts in local government about the UK government’s commitment to smart cities. Everyone will be watching the Chancellor’s Autumn statement and the development of the government’s industrial strategy.

The Mayor of London supports his city’s continued involvement post-Brexit in trans-national programmes like Horizon and then it will be about how the UK continues to contribute and take part in them in a similar fashion to that of Norway, for example.

“I am a firm believer that city-to- city collaboration is only just getting going,” continues Collinge. “I think it’s incumbent upon us, whatever happens and whatever form Brexit takes, that cities find a way of working together on things that are of mutual advantage to us.”

Triangulum’s project leader Duncan hammers home the message: “As a city, Manchester will continue to build and value our international partnerships and networks and will work very hard to remain an outward looking, international city.”

While 52 percent of the UK population might be keen to distance themselves from Europe, it is clear that those working in the smart cities community want to retain the links they have been building with their European partners. But while such links may help UK cities to learn about projects, it is their EU counterparts who will be accessing the smart money to pay for them.