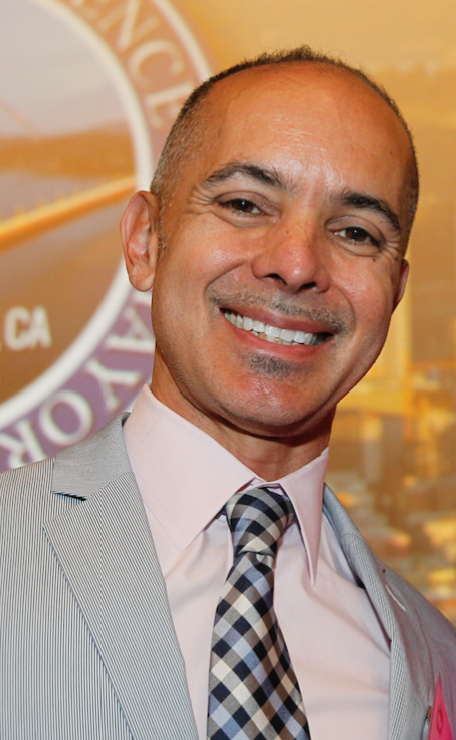

Photo: Screen-Shot-2015-12-15-at-11.52.58

Using food to drive urban innovation

07 December 2015

by Jonathan Andrews

Farmers’ markets, ‘farm to fork’ and food trucks are all the rage in many US cities but, as Jonathan Andrews reveals, two cities are taking the foodie trend to a new level by using it to drive local economic development.

Louisville, Kentucky, famous for bourbon, the Kentucky Derby and an important Ryder Cup golf win in 2008, was also once renowned for its high-quality tobacco leaves–when smoking was considered a social habit.

“At one time the number one cash crop was tobacco,” explains Greg Fischer, Mayor of Louisville. “You could have a very small farm, produce tobacco and support a family. With the move against tobacco, farmers were paid not to produce tobacco, so as a result, Kentucky had more small farms than any other state in America.”

But with the decline in tobacco use, the mayor has found a new use for these small farms which are now being used to produce food. Louisville conducted a study that found that each year city residents consume US$2 billion worth of food. Almost US$300 million of this is being spent on local foods but there was a further US$500 million demand not being met by the local supply.

“I felt like this was an area to concentrate on and emphasise,” says Fischer. “When I was running for mayor fve years ago, our restaurants were starting to get national acclaim and there was a lot of development in local food initiatives. You could see that it was growing and was going to be big.”

Two years of discussions and “kicking around ideas” led to the concept of the West Louisville Food Port being born, due to begin construction in Spring 2016. More than a food hub, the project envisages aggregation, distribution, storage and marketing–all typical of food hubs– but adds farming, on-site processing, a community kitchen, retail, recycling and its own anaerobic digester that will produce energy.

“Like ships come into a port, all food will come into a port,” explains Fischer. “We have some food ports in America and what they do typically is aggregate or bring food into it, then distribute it out. We are adding to these functions like farming and some food processing, like turning apples into apple sauce. It will create 250 jobs from the local area, which is located in the lowest income area of the city. Many people think that it is controversial but I think it is smart.”

The US$58 million food port, financed by a mixture of public and private investments, including Seed Capital Kentucky, will be housed on a 10-hectare piece of land that was ironically the city’s tobacco distribution centre. As an example of the lack of investment in the area, 100 years ago the land was worth US$2.5 million. The city bought it in 2013 for US$1.5 million.

Many Kentucky farmers are looking for alternative crops since the decline of the tobacco base,” says Teresa Zawacki, Senior Policy Advisor, Louisville Forward. “the food port will create market opportunities for farmers growing food in many of the same ways that the site provided markets for those same farmers when they were growing tobacco.”

Seed Capital Kentucky is still finalizing the remainder of the financials to build the port, but Zawacki is adamant that this won’t be a deterrent. “There is a combination of tax credits, equity and debt that needs to be secured before the project can move forward, although those conversations are underway,” she says.

The city is also implementing policies, such as low rents to incentivise and turn the port into a food innovation district, to help people interested in food start their own business. A community council was formed to ensure local ownership and buy-in for the project. Eighty percent of the 250 jobs on offer are to be filled by people from the neighbourhood.

“The spin-off is to, frankly, see people feeling more interconnected from different parts of town with our lower income part of the city,” says Fischer. “The problems in urban America are not a secret and we fortunately have not had anything like as severe as in Baltimore [the April riots]. One of the best ways not to see that happen is to have people feel connected with each other and with the economy. This is about more than just food.”

Another angle the mayor hopes to see come to fruition is a boost in tourism. Already considered one of the top ‘foodie’ cities in the US, tourist numbers have grown from 250,000 to 750,000 over the past five years, with most coming to taste bourbon and enjoy food. The mayor hopes to increase this to two million a year by 2020. “What any mayor wants to have is an authentic city,” comments Fischer.

“When somebody comes to their city they want an experience like none other. The transformation of the neighbourhood is number one, integration into our bourbon tourist experience is number two, and number three is to develop hundreds of jobs for the food port and innovation around that, and then to have national and international recognition as a place for innovation. They are our goals.”

From boutique to business

On the other side of the country in the heart of the nation’s food bowl, West Sacramento in California is helping to turn food deserts and vacant lots into more than just small boutique urban farms, by providing land for newly graduated farmers to set up their first business.

“Our region is the most productive agricultural region in the US, however we consume less than five percent of our food locally,” says Chris Cabaldon, Mayor of West Sacramento. “We produce so much food and consume virtually none of it; our region was heading toward problems in food security and health.”

Like Kentucky, California had a history of farming. The skills and the land would be passed down through families but as agriculture turned to agribusiness, skills were lost. While the demand for farming is back, mainly from young people like ‘hipsters’ and ‘foodies’ that care about the environment, localness and sustainability, the education and knowledge was missing. To fill this gap farming academies were established.

“However, once they graduated from farming, then what?” asks Cabaldon. “They don’t own a farm, they aren’t going to inherit a farm, they can’t get a loan from a bank to buy a farm, they have no relationship with the bank, restaurants, supermarkets or grocers. There was a fundamental gap in the system of career training for farming because we never had to have one before.”

A second problem identified by the city was the question of whether or not they could produce more food, both on the urban edge and also within the city. While there were numerous vacant lots of land, these plots were highly valuable, of which farming was not seen as the best use of the land in the long-term.

Rather than turn city land to agriculture permanently and hence miss out on generating tens of millions of dollars of taxes from other income and economic activity, the city took the decision to use vacant lots as temporary farms. Working in partnership with the Center for Land Based Learning, the first incubator lot was opened in 2014 on a quarter of a hectare, winning the US Conference of Mayors Green Space Award. The initiative has now grown to a dozen farms that total nearly three hectares, producing tonnes of produce.

“It’s the first [initiative] that I’ve known of that is actually trying to turn urban farming into a lucrative business opportunity for small farmers,” says Sara Bernal, Programme Manager, West Sacramento Urban Farm. “We focus on production and help them operate as a small business, like an apprenticeship, to build capital and business relationships.”

To help match farmers with available land, both from government and the private sector, the city is working with Code for America to develop technologies, including an app.

“Remember this isn’t land that is up for sale that’s being sold on the real estate market,” says Cabaldon. “We’re working on the technologies that will match property owners that are willing to let their land be used for a transitional purpose. We’d particularly like these to be in food deserts where there is very little access to healthy foods.”

The farms donate to food banks and sell to residents of food deserts at below market prices. Farm stands are also used where farmers can sell their produce and receive support from two local supermarket chains. To help farmers, restaurants, grocers and supermarkets know what is being produced, where, and at what cost, the city is now looking at ways to aggregate this data.

“A high school, for example, when it’s building its menu for its students, can look at this in the same way as when its staff go to a food factory,” says Cabaldon. “They can aggregate all that data together and express back to the urban farmers what their long-term demands are. The farmers can then adjust what they are growing based on the demand. We are building real, functional markets.”

To help the farmers better connect with restaurants, Bernal’s latest grant proposal (submitted in August) is to farmers will have access to cold storage and be able to serve larger networks, like school districts, hospitals and larger office blocks. The city has also waived fees for installing the water infrastructure, like meters, which saves a farm anything from US$30,000 to US$75,000.

“We are building economic redevelopment in these neighbourhoods, removing crime and blight, activating development parcels that have otherwise been sitting vacant for decades,” adds Cabaldon. “We’re creating real employment for people who want that employment. We’re creating markets that are sustainable and are based on sound economic principles, and creating an opportunity for companies that want to get involved with food innovation, food security and community participation.”

Despite Louisville and West Sacramento taking different approaches to food, both concepts share the same ultimate goal of using innovation to improve the economy and lifestyles in both cities.

“What we are doing is using food as a unifying medium for the metropolitan and rural areas of our city,” adds Fischer. “This leads to healthier public policy decisions, and using food as a medium is a natural way for that to happen.”