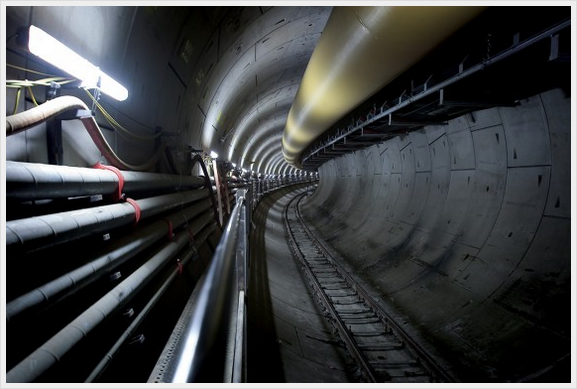

Photo: Londons-Crossrail

Plugging the infrastructure gap: How can cities attract private investment?

25 September 2014

by Richard Forster

Traditional sources of city infrastructure funding from central governments and big banks have been badly affected by the global financial crisis, so cities need to look at innovative ways of securing the necessary funding. Jonathan Andrews and Richard Forster explore how with better governance mechanisms and greater revenue raising powers, local governments can begin to attract the institutional investment, which is critical to their development

From the tedious road transfer from JFK airport to New York City to the poor air quality of Paris which led to emergency measures earlier this year, from streets choked with traffic in Jakarta, São Paulo, Mumbai and Moscow to the smog over Lagos and Beijing, all cities, both developed and developing, are facing up to a financial deficit in meeting their infrastructure needs.

According to the World Economic Forum, global spending on basic infrastructure is US$1 trillion short of where it needs to be. The OECD reports that the total amount of infrastructure financing needed, will hit US$65 trillion by 2030.

“Clearly public investment is not enough to bridge the gap, when you consider that official development assistance stands at about US$135 billion today,” says Joshua Gallo, municipal finance specialist in the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) at the World Bank. “We need private investments. The global investment industry holds assets worth well in excess of US$100 trillion, looking for long-term investments that are creditworthy.”

Investor Ready Cities, a report released in May by technology company Siemens, international consultants PwC and law firm Berwin Leighton Paisner, says that cities need to harness private sector expertise and investment and look beyond their domestic markets to the global investment industry including sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, multilateral institutions, and private capital. But how can cities start to tap into such institutional funding? How can they demonstrate that they are a creditworthy investment?

The report recommends that for cities to attract such investment it is essential that they put in place transparent and even-handed governance systems backed by proportionate strategic planning and regulation, which offers appropriate comfort to investors on land use and other rights. And of course all of these foundations need to be capped with innovation to provide a business model which can give investors the returns they need.

“It’s about cities understanding where they are relative to the expectations and requirements of investors looking to invest in the city or in particular infrastructure programmes,” advises Mukhtiar Tanda, Partner at Berwin Leighton Paisner, and a lead author of the report.

London’s Crossrail project was highlighted as a best practice by the report for both its innovation and holistic management which will see the construction of 42 kilometres of new rail tunnels for Europe’s largest urban infrastructure project under the streets of the UK capital. By the time it is completed, in 2018, the final cost is expected to be nearly £15 billion.

Through value capture schemes, incorporating compulsory developer contributions as part of the Mayoral Community Infrastructure Levy and a generally levied Crossrail Business Rate Supplement for businesses benefitting from the upgrade to local stations, London has succeeded in introducing financial mechanisms to support the necessary infrastructure development.

As a result, despite London’s rising debt level to fund Crossrail including a £3.5 billion loan, the city was able to retain its AA+ credit rating from Standard & Poor’s, a rating agency, which analyses the credit risk of governments, cities and companies.

“The Greater London Authority was able to charge additional business rates and that money was then ring fenced for it to service the related borrowing,” explains Hugo Foxwood, Associate Director for International Public Finance at Standard & Poor’s. “Consequently the committee felt that the affordability of the debt service, supported by the stability of the revenue stream, broadly offset the risks associated with debt levels.”

Additionally the Investor Ready Cities report praises the management by Transport for London and the Mayor’s office which has enabled decisions to be based on what is considered to work best in overall transport terms rather than simply in the best interests of the operator of a particular mode.

“Governance and legal frameworks are very important precursors, if not a very important part of the mix itself which is often overlooked,” explains Tanda. “If these concepts are planned holistically from the outset, problems in attracting finance can be forestalled, and projects will be easier to deliver.”

Getting your house in order

The Peruvian capital, Lima, is one city that set out to improve its own governance structure and operational performance in order to become more attractive to investors. In 2006, the city began updating and improving its tax and non-tax collection strategies to boost revenue while rationalising expenditure. This included updating taxpayers’ assessments, improving accounting practices, putting in place new revenue collection networks and adopting sound debt and treasury management practices.

“The performance of a city is not a financial issue, it’s also a corporate issue, one of corporate governance,” says Cesar Marcovich, advisor to the finance department in Lima’s municipal government. “The improvement of the [credit] ratings is the result of delivering corporate qualities adopted by the municipality.”

Marcovich attributes Lima’s new and highly popular bus rapid transit (BRT) system to the reforms that were undertaken, which led to loans from Spanish bank BBVA and Banco del Credito de Peru. US$160 million of the US$350 million total budget came from the city itself after improved tax collection methods boosted its own investment resources.

“Lima’s funding capacity was enhanced by introducing corporate governance management policies and sound fiscal and financial management which boosted local tax income collection,” he adds. “These achievements also led to lower financial costs and longer term loan maturities obtained after investment grade ratings of BBB- [Fitch] and Baa3 [Moody’s] were achieved in 2011.”

The all-important investment grade credit rating, however, is still a long way off for many cities. Yet, is too much emphasis put on credit ratings?

“Credit ratings are what cities receive at the end of the line,” says Gallo from the World Bank. “We need to focus on the beginning and help cities get the fundamentals right. Once cities are able to enhance revenues, rationalise expenditures, leverage assets and better manage debt, then credit ratings will not be an issue.”

According to the World Bank, many municipal governments in the developing world cannot access capital markets or international debt funding. Of the 500 largest cities in developing countries, only a few are considered creditworthy, with just 4 percent having access to international financial markets and 20 percent able to tap local markets.

To help cities achieve creditworthiness, rather than just a credit rating, the World Bank set up a City Creditworthiness Program in October last year as part of its Low-Carbon, Liveable Cities Initiative. Its long-term goal is to help cities achieve ‘climate smart development’.

In Kampala, Uganda, the World Bank has assisted the city with revenue mobilisation. In one year the city has increased its revenue by 86 percent year- on-year, almost doubling its debt capacity and improving its ability to invest in climate-smart infrastructure.

“In many ways this is the ‘real’ impact that cities can expect as they pursue creditworthiness,” says Gallo.

Apart from offering creditworthiness academies, the World Bank is assisting cities in addressing immediate financing needs to develop mechanisms to attract more private capital to the municipal, or sub- sovereign, market. This includes pooling financing opportunities and connecting cities that want to finance the same type of investment, such as LED traffic lights, allowing them to access the market together at better financing terms.

Role of development banks

In many developing countries, development banks are still the primary and often the only source for concessional finance, due to immature domestic capital markets, where borrowing by cities requires extra support.

The International Development Finance Club (IDFC), a new network of 22 national and regional development banks established in 2010 (see box), has set up working groups to focus on sustainable infrastructure and sustainable urbanisation. According

to Holly Williams, Executive for Institutional Funding at the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF), which heads the IDFC working group on sustainable infrastructure, many local and municipal governments in developing countries struggle to obtain long-term financing due to factors outside of their control, including currency risks and underdeveloped domestic financial markets.

The International Development Finance Club (IDFC)

The IDFC is a CEO-led grouping of 22 regional and national development banks chaired by Ulrich Schröder, who is CEO of KfW, the German development bank. The group came into being in 2010 with members drawn from all continents including high-level representatives from the BRICS countries comprising Hu Huaibang, CEO of the China Development Bank; Patrick Dlamini, CEO of the Development Bank of Southern Africa; Luciano Coutinho, President of BNDES, the Brazilian development bank; Vladimir A. Dmitriev, CEO of Russia’s Vnesheconombank and Navin Kumar Maini, Deputy Managing Director of the Small Industries Development Bank of India. For further information, see www.idfc.org.

“As they [development banks] are aptly suited to absorb more risk than the private sector, [they can] play a key role in mobilising resources for local governments,” says Williams. “This is done by offering risk insurance and guarantees, providing competitive local currency debt financing and backing more innovative development finance approaches and tools, such as PPP [public private partnerships] policy framework reforms and frontier project finance models. They can also structure pooled financing schemes that help support domestic credit markets by providing local funding partners with an improved level of creditor status.”

According to the IDFC, national ministries in many developing countries do not provide high quality, long-term planning, investment programming or adequate maintenance. Where institutionalised norms and regulations exist, many exhibit weak compliance supervision. The IDFC emphasises the importance of decentralised management, local autonomy over financing, and the inclusion of end-users and citizens in the decision making process particularly in the case of urban transport.

“Local governments are more accountable for their own development when the funds are raised locally, rather than at the national level,” explains Williams. “IDFC members commonly stress the importance of local autonomy over financing, and the inclusion of customers and community members in the decision making process to promote more service oriented reform and widespread public support for development projects.”

Where should cities start?

Simple steps are advised by Berwin Leighton Paisner’s Tanda when cities begin the long trek towards creditworthiness. He warns they need to be mindful of tailoring to local conditions when establishing their legal governance frameworks, rather than elaborate options, before they step out and engage with the wider market.

“Cities should focus on simpler models that may not exactly be very pretty but are fundamental to get things moving,” says Tanda. Tanda emphasises that setting up a legal framework is all well and good but meaningless without deep cultural change within government and provision of the correct training to those people in authority.

“Without the machinery of governance being in place to support the legislative or legal framework, then the concept of ‘investor ready’ becomes merely illusory. It’s like downloading a highly tuned engine of legislation into a car that doesn’t have any wheels.”

The World Bank notes a direct connection between improving financial management–such as local government municipal revenue collection–and the raising of private capital for infrastructure.

“For Harare, our major problem is collecting taxes and fees and we have a greater amount of mandatory expenses than what we can collect,” says Assumpta Gwatiringa, Senior Accountant for the City of Harare, Zimbabwe. She is not alone. Close to 80 percent of the municipalities represented on the World Bank’s Creditworthiness Program say that their city consistently runs an operating deficit.

“We have many big problems in Maputo,” explains Gracia Teresa Manguele, the head of revenue of the Maputo Municipality in Mozambique. “Chief among them are a critical lack of planning in our spending, the size of the informal economy, and the need to register properties for tax purposes.” Only about 3,000 of Maputo’s 200,000+ properties are currently registered.

Building on the results of an in- depth self-assessment of their cities’ finances, participants at the first edition of the Creditworthiness Training Program for African Cities, which took place in October last year, developed a multi-year action plan to address challenges to achieving or enhancing their creditworthiness.

Each action plan is tailored to a city’s specific context and challenges, providing technical assistance on issues such as revenue and debt management, improved expenditure control and asset maintenance, capital investment planning, as well as transaction planning, structuring, and execution.

The City Creditworthiness Program aims to help with the identification, collection, and management of ‘own source’ revenues, as well as with strengthening the administration’s financial management policies and practices. The programme can also assist entities ‘ring-fencing’ revenue sources to structure debt transactions for investment projects. Finally, it will support coordination with central governments to improve legal and regulatory frameworks that empower city administrations to collect revenues and issue debt responsibly.

“Most African cities are invisible to investors looking for opportunities in sub-sovereign capital markets,” says James Close, Programme Manager for the PPIAF, at the World Bank. “This initiative has the potential to leverage private investment that will finance the infrastructure necessary to help cities meet the demands of citizens for basic services, and build resilience to the effects of the changing climate.”

Gallo says that understanding the implications of financial practices on creditworthiness is the precondition to set municipalities on the path toward strengthened fundamentals and improved performance. “Cities will not be able to achieve creditworthiness overnight,” comments Gallo. “It is a long trajectory, which requires strengthening of fundamentals, improving revenues, financial management, and debt management and we are committed to supporting cities throughout this process.”

Green city bonds

Another important consideration in attracting investors is sustainability: some cities have started to use the green bond markets to fund infrastructure projects, and they must adhere to an independent verification process to certify that the application of the funding is for suitable green projects, which if handled right can open up a new swathe of investors to provide the funding they may need.

In June, Johannesburg and Gothenburg both tapped the bond markets for green finance with the latter having launched Europe’s first green city bond in September 2013.

Demand for Gothenburg’s second issuance of SKR1.8 billion (US$264 million) on 8 June was taken up by institutional investors across Europe with the funds set to support the city’s environmental programme in areas such as renewable energy, public transport and waste management. Gothenburg has been a long-term issuer in the Eurobond markets but green bonds have added a different dimension to the investor base with city residents even asking if a retail offering would be possible in future.

“For the first bond, investors came from Switzerland, Germany and Sweden and for the second it was Switzerland, Sweden and Norway and for the investors the allocation by type was asset managers, bank treasuries, insurers, pension funds and private banks so we actually reach out to new investors,” says Magnus Borelius, Head of Group Treasury in the City of Gothenburg.

As well as obtaining an independent review of the bond issue ahead of its launch from the Oslo-based research centre Cicero, the city must provide continuous post-launch reporting to investors on how projects are developing. The funds from the SKR500 million issue in September 2013 were allocated to a large biogas project and a smaller electric vehicles project, which aimed to put 100 vehicles in local authority use across the city.

“When we issue the bond we don’t tell the investors which particular project the funds will be invested in but that it will be in these areas and then through our annual report, our investor letter and our webpage, we highlight the [specific] projects that are benefitting,” explains Borelius.

Johannesburg’s 1.46 billion Rand (US$138 million) issue was 150 percent oversubscribed and the funds will be support a biogas to energy project and the Solar Geyser initiative as part of the city’s climate change mitigation strategy.

The World Bank put together the original concept of green bond finance in 2008 and with its emergence as a tool for cities, Cities Today will provide a detailed case study and report in the next issue for cities looking at this type of emerging finance.